Dave Rupert, Write about the future you want:

There’s a lot that’s not going well; politics, tech bubbles, the economy, and so on. I spend most of my day reading angry tweets and blog posts. There’s a lot to be upset about, so that’s understandable. But in the interest of fostering better discourse, I’d like to offer a challenge that I think the world desperately needs right now: It’s cheap and easy to complain and say “[Thing] is bad”, but it’s also free to share what you think would be better.

Co-signed.

This is not my beautiful agent-driven economy

We’re in a weird agent coding moment here. AI maximalists are putting wild, often incoherent, projects out there. Some, seemingly replacing their writing output with LLM-trained output. (I don’t understand the temptation to that one at all. The interesting thing about writing, as with any performance art, is risk!) Others, merely annoying the heck out of each other with crustacean emoji.

It feels like we’ve got two groups pursuing entirely different paths to the next level of agent coding. Both camps are not even wrong:

- The open problems path: we need to figure out correctness, guardrails, what this means for teams, etc. Only then can we be certain we’re not just burning tokens in pursuit of software we’ll have to clean up or write off as brown-field development in the next 3–6 months. This isn’t even the AI safety crowd of 12–18 months ago. I would have called these folks pragmatists just a couple of months ago.

- The maximal/acceleration path: figure out how to get the agents working faster so that they solve the problems for us. Build the system that solves the problem, mostly through throwing more agents and tokens at any given problem. These aren’t the (non-political) accelerationists who foresee AI and blockchains coming together to allow people to nope out of civilization and run their own AI-enabled private cities and enclaves. I would have called these folks the hype train conductors a few months ago.

I’m inclined to pursue open problems (validation and verification, collaboration, guardrails) before dialing up the output and delegation (orchestration and parallelism). The silver lining is we’re going to find out (possibly quickly) which camp is relatively right (Has Some Good Points) in addition to not even wrong. 🙃

Below, some solid ideas others have had about this tension between “well there are open problems…” and “…jump in with two feet anyway!”.

Justin Searls asked when we would see this kind of surplus of software production and surfeit?/deficit of taste. It seems like it’s just around the corner and the two following links are the early recognition. In other words, he was only off by a few months.

Armin Ronacher, Agent Psychosis: Are We Going Insane?:

The thing is that the dopamine hit from working with these agents is so very real. I’ve been there! You feel productive, you feel like everything is amazing, and if you hang out just with people that are into that stuff too, without any checks, you go deeper and deeper into the belief that this all makes perfect sense. You can build entire projects without any real reality check. But it’s decoupled from any external validation. For as long as nobody looks under the hood, you’re good. But when an outsider first pokes at it, it looks pretty crazy.

It takes you a minute of prompting and waiting a few minutes for code to come out of it. But actually honestly reviewing a pull request takes many times longer than that. The asymmetry is completely brutal. Shooting up bad code is rude because you completely disregard the time of the maintainer. But everybody else is also creating AI-generated code, but maybe they passed the bar of it being good. So how can you possibly tell as a maintainer when it all looks the same? And as the person writing the issue or the PR, you felt good about it. Yet what you get back is frustration and rejection.

This is what I’ve been saying since the summer. We are in the middle of software engineering’s productivity crisis.

LLMs inflate all previous productivity metrics (PRs, commits) without a correlation to value. This will be used to justify layoffs in Q1/Q2 of this year.

2026 gonna be wild, and we’re only one month in.

I’ve been reading Power Broker on and off throughout the year (brag). I’m almost five hundred pages in (brag again) and it’s worth it. The writing is as good as the research is deep. Which is to say, it manages to maintain a great pace even though it’s a huge book (brag the third). Caro’s pacing, by alternating between moving the Robert Moses story ahead and adding color by telling the brief story of the minor characters involved in Moses’ story at the time.

Furthermore, Robert Moses was a real jerk. And, a bully. 🤦♂️ Same as it ever was.

I’m continuing with the Dune chronicles. Children of Dune seemed like all setup and only perfunctory pay-off. God Emperor felt like it had more to say, whether it’s philosophical or political. The three thousand year jump ahead is a lot, though!

As a palate cleanser between Dune novels and Power Broker chapters: just started Liberation Day by George Saunders and Iberia by James Michener. 📈

If you have significant previous coding experience - even if it’s a few years stale - you can drive these things really effectively. Especially if you have management experience, quite a lot of which transfers to “managing” coding agents - communicate clearly, set achievable goals, provide all relevant context.

Based on my own experience and the industry news, it’s not a great time to look for engineering management work. But, based on a sample size of one, it’s a good time for engineering leaders/managers to ride the EM/IC pendulum back to IC work, with a leadership twist.

I’ve been calling this “engineering leadership, the good parts”. More of the activities that produce software, for people, amongst teams, less of the activities that allow software teams to exist within larger organizations and business hierarchies. Pairing those skills with teams of people and coding agent collaborators is pretty potent these days.

Pro-tip: if you’re an IC who is really enjoying this agent stuff, you could be a future engineering leader!

Processes should serve outcomes, not the other way ‘round

In moments where process overwhelms a team’s ability to get stuff done, I’ve been fond of saying we’re not here to:

- Push Trello cards around.

- Guess if a coding task is more like a small t-shirt or a large burrito.

- Arrange our git commits in just the right order.

- Write long-lived documentation.

I’d suggest that, instead, we’re here to ship code.

Now that writing code isn’t the tricky part, I’m more convinced than ever we are both not here to operate a process and that activities like these are more important.

I never claimed my aphorisms were consistent or even logical!

Somehow, it was only within the last month that I stumbled upon a better saying. We’re not here to write code, operate processes, recite our statuses in meetings, etc.; we’re in the software development game to make outcomes. In particular, the outcomes you might expect of a software-technology company, if you’ll pardon some light hype-y jargon. Shipping code is a small part of that, but it’s in service of fixing problems, improving efficiency, solving new problems for customers, or putting an invention into the world.

I was going to include checklists in the list of things we’re not here to do. But, checklists are a pretty great way of thinking, and often lead to their intended outcomes. When they don’t lead to those outcomes, it’s typically easy to look at the items in the list and see why! “Oh, we skipped this safety check and things went sideways” or “we didn’t do the user research and, predictably, users weren’t sure what this feature is for.”

By contrast, documents, processes, and quality gates typically obscure your organization’s intended outcome. They’re too frequently a trade-off to prevent getting burnt in the same way as before. Which is probably why they correlate so frequently with failing to hit or losing track of the positive outcomes that matter.

“We’re here to learn” is a good proxy for “we’re here to generate outcomes”. If a checklist (or process or document, if you must) helps you learn more about customers/markets/your design/the world/etc. faster, it’s probably a good thing for you. If it prevents success and failure in equal probability density, it’s likely overhead.

I (was) back at Destiny 2, since they’ve fixed many of the daily gameplay loops and put Star Wars in there. (Not even the most bonkers statement of 2026, somehow.) The odd thing about Bungie nailing the landing of a ten-year video game saga is that years 11 and 12 leave me wondering if I now is the time to bow out, even if years 19 and 20 prove as solid as years 9 and 10.

I took up autocross over the summer, enjoyed the challenge and community therein. I am a pretty slow driver, but it’s the best way to enjoy a sports car I’ve yet found. There’s always a few seconds to find!

Since the season is over here in the cold and rainy northwest, Gran Turismo 7 is filling in. Again, I’m not the fastest, but the practice-like activity ain’t bad. Again, there’s always seconds to find. The “let’s do longer races” add-on released in November to Gran Turismo 7 is pretty good too. But, as of lately, I’m trying to do stuff other than video games, so the PlayStation stands idle.

Recently good shows: The Lowdown, Alien: Earth, Pluribus. Currently, re-watching Better Call Saul. I don’t really like the Chuck and Jimmy arc, but the Jimmy becomes Saul arc is one of my favorite out there.

Bobcat, a document editor prototype

Recreating the Canon Cat document interface really lived in my head for a few days there. To such an extent, I’ve been building prototypes based on the idea and exploring the adjacent space.

Thus, my remix of the idea, Bobcat. She may not look like much, but she’s got it where it counts. I’ve added some special modifications myself. 🤓

It’s got a big text field, forward/backward buttons, and a tiny text field for changing the text marker to navigate with. Not quite as sophisticated as Canon Cat, but it’s a start.

Most of this was vibe engineered. I sketched out the first iteration with my pretty limited, but workable, SwiftUI chops. From there, almost all the document-centric app code, was a Claude Code thing.

I feel a little awkward about that. I wish I were “brain coding” more, but the whole point here is to experiment in the material – Swift UI and document editors. Working with an agent gets me there faster, so I go with it. Per delegate the work, not the thinking, I’m exploring ideas that would take me weeks or months to figure out if I was writing SwiftUI on my own. If the ideas bear fruit, I’ll pick up SwiftUI as I go. If not, more of my brain is available for whatever ideas do stick.

What’s next for this prototype? Keep tinkering with building macOS things, explore more ideas like scripting and data models, and lots more iteration.🤞

It’s the end-game of typing code as we know it

And Thorsten Ball feels fine. Joy & Curiosity #68:

2025 was the year in which I deeply reconsidered my relationship to programming. In previous years I had the occasional “should I become a Lisp guy?”, sure, but not the “do I even like typing out code?” from last year.

…

And the sadness went away when I found my answer to that question. Learning new things, making computers do things, making computers do things in new and fascinating and previously thought impossible ways, sharing what I built, sharing excitement, learning from others, understanding more of the world by putting something and myself out there and seeing how it resonates — that, I realized, is what actually makes me get up in the morning, not the typing, and all of that is still there.

I’m still adapting to this, having previously identified as a “Ruby guy”, “a Vim enthusiast”, and “a TDD devotee”. A couple of times a day, I find myself executing the “careful, incremental steps” tactics that scarcity of code demanded. And then I wonder, what’s the corresponding move for abundance of code? (I think 2026 is, for me, likely about exploring and finding that answer.)

I learned from a couple turns as an engineering manager that it’s the problem-solving, technical and social, that really excites me. If using coding agents means I code and think about the particulars of software development less, in exchange for writing and thinking more about what’s possible with software and teams, that’s a fine trade-off.

What if we don’t have to worry about how often someone or something would have to redo a contribution? What if we don’t have to worry about in which order they produced which lines and can change that? We’ve always treated auto-generated code different from typed-out code, is now the time to treat agent-generated PRs and commits different? What would tooling look like then?

I’m with Simon Willison here: what we produce now as software developers is trust-worthy changes/contributions that do the thing we say they do and don’t break all the other things.

Most teams are over-indexed on “produce code” and short on “make sure we didn’t break other things” part. I suspect, for a few months/years, we’re going to see lots of (weird) ideas about how to shift from scarcity of code to scarcity of verification. I’m not sure that coding agents can help us slop/generate our way out of that, at least not in January 2026.

Joining a new crew amidst a sea change

I joined a new team as a staff software engineer a couple of months ago, huzzah! Some reflections:

I’m writing TypeScript and Python, after many years of Ruby with a touch of JavaScript. Types are, after about 25 years of software development, part of my coding routine. They’re not so bad these days. It finally feels like types are more helpful than a hindrance.

Thankfully, this code is not too long in the tooth, so the dev loop is fast and amenable to quality-of-life improvements. But, it’s a big, new-to-me codebase and a deep domain model. I wouldn’t get much done were it not for coding agents, their ability to help me discover new parts of the code, and having spent much of the past several months practicing at steering them. So all that Claude Code experimentation was time well spent!

The team uses Cursor. I gave it a try and am mostly onboard with it. I still think JetBrains tools are more thoughtfully built than VS Code and its forks. But, Cursor’s agent/model integration is pretty dang sweet, I can’t argue with that.

And, Cursor’s Composer-1 model is fast and sufficiently capable. I think there’s something to be said for faster models that can work interactively with a human-in-the-loop. Cooperating with the model more like the navigator in a pair programming situation than a senior developer vetting the work of a junior developer. It feels like OpenAI/Anthropic/etc. really want to show off how long their models can work unattended. But I think that only magnifies the problem of reviewing a giant pile of agent-generated code at the end.

I suspect this is going to change our assumptions about tradeoffs on ambition and risk. If we’re lucky, we can replace a lot of soon-to-be-legacy process and ceremony that was about hedging and had nothing to do with the quality of product or code at all.

I wonder: besides wishing code into existence, which costly things are now cheap-enough? Agents reviewing agent-generated code doesn’t work that well yet. But, agents can tackle refactors, documentation writing, and bespoke tool creation. All the things we’ve previously been forced to squeeze into the time between projects. The cobbler’s children can now have pretty good shoes.

The hand we dealt

My parents (and their parents) world seemed more stable, somewhat knowable. (It probably wasn’t.) Even if your situation was low agency, if you did what you were supposed to (the life script) long enough, then things probably ended up alright. Scarcity before, abundance later.

My generation (millennial or X) and the ones adjacent came along and accelerated things. Stability declined as dynamism and knowability were within easier grasp, yielding greater individual agency. But now change was the only constant. More folks did what they wanted to and got by. But playing the life script, doing what you were supposed to do, was still pretty effective.

Jury’s out whether that will collapse just as these generations retire.

The next generation are going to change the balance too. What we gave them, in terms of technology and culture and politics and the environment, could make for wild, weird times. I don’t think we should besmirch them too much, if possible, for what they do with it. If anything, we should find harmony with how they played the hand we dealt.

Three great clarinet-adjacent sentences

I DID NOT KNOW what was going to come from Angela’s clarinet. No one could have imagined what was going to come from there. I expected something pathological, but I did not expect the depth, the violence, and the almost intolerable beauty of the disease.

– Kurt Vonnegut, Cat’s Cradle

Coding for the sake of typing in code

It’s not gone, but it’s on the way out. Brain coding is now: modeling, system design, collaboration, and problem solving. And increasingly: context switching, mentoring and coaching, delegation, execution, continuous learning.

Spicy but, with some reservations, I agree:

I believe the next year will show that the role of the traditional software engineer is dead. If you got into this career because you love writing lines of code, I have some bad news for you: it’s over. The machines will be writing most of the code from here on out. Although there is some artisanal stuff that will remain in the realm of hand written code, it will be deeply in the minority of what gets produced.

– Paul Dix

If you ever had “artisan” or “craftsperson” near “code” in your identity, then buckle up. You may find the next years challenging and un-fun. (I had “Expert Typist” for quite some time in mine. Ouch.)

…virtuosity can only be achieved when the audience can perceive the risks being taken by the performer.

A DJ that walks on stage and hits play is not likely to be perceived as a virtuoso. While a pianist who is able to place their fingers perfectly among a minefield of clearly visible wrong keys is without question a virtuoso. I think this idea carries over to sports as well and can partially explain the decline of many previously popular sports and the rise of video game streaming. We watch the things that we have personally experienced as being difficult. That is essential context to appreciate a performance.

– Drew Breunig, A Comedy Writer on How AI Changes Her Field

There is a certain virtuosity in someone who can put a lot of code out there quickly. But, only in the sense that they can “avoid all the wrong keys”, taking the most direct path to solving the problem or learning more about the domain. Navigating false paths, writing the right code for the moment, no more or less than neeeded, is the thing. Whether it’s an agent or a human, pumping out tons of code that requires thorough review for style and purpose is no longer the game.

I suspect this means that writing, film-making, and music are unlikely to fall victim to generative AI. At least, in the scenarios where art is the draw. Ambient music of all kinds, for airports or beer commercials or in-group signaling (looking at you, save a horse/ride a cowboy) are all probably going drastically change due to generative AI. The same for writing that isn’t trying to say something and moving images that exist only to fill in the time.

Perhaps, more than ever, data is the asset. We could delete a lot of the code as long as the data remains accessible and operations continue. 🤔

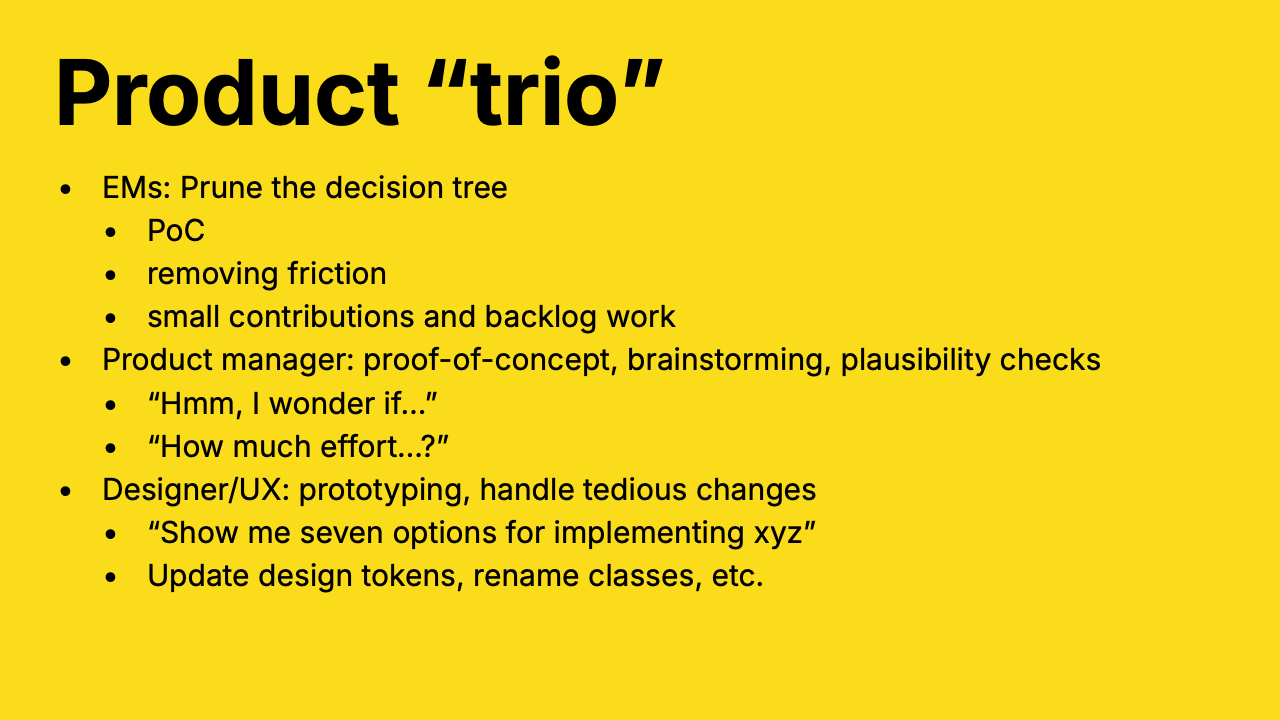

The whole product team can use coding agents

This is an expansion of a talk I did for Portland AI Engineers in October. The gist of which was, coding agents are for the whole product team. Not just coders!

Once upon a time

Over 14 months of job searching, I tinkered and experimented with what has become agent coding or vibe engineering. My hypothesis was that, if the hype is real, nearly zero’ing out the effort required to type in code would drastically change how software teams collaborate.

In particular, anyone with a leadership hat (engineering managers, staff+ engineerings, product managers) would have more tools at their disposal. That could lead to better decisions earlier in projects. Fewer bad decisions right when making the wrong choice can generate costly path dependence and sunk cost problems.

I set out to reproduce how folks use coding agents to reduce the effort required to build software. This started with prompt-and-paste in ChatGPT and then Claude. The real moment of drastically reduced friction was the release of Claude Code. That’s when I jumped all the way in and found that perhaps the hype is not hot air.

Now the question, for prospective software projects, has become: can we go from “this is not a bad idea, on paper, should we put a team of software developers on it?” to “this kinda works, let’s move forward” or “actually, bad idea, never mind” in hours instead of days or weeks?

I think the answer is yes!

Coding agents – not just for coders

The whole product team can, and should, use coding agents. Leadership should consider updating how they work to include doing first-pass collaboration with coding agents to explore, develop, and validate their ideas.

For non-developers in particular, the potential is tremendous. It’s never been easier for those who can sling a little bit of prose to make code. More on how they might do that in a moment.

There are many qualifications to that statement, which I’ll get to forthwith.

You have to bring the right mental model, set expectations based on your own experiences, and try new things as your peers (colleagues and otherwise) demonstrate & validate new approaches.

Am I holding this right?

As they say in memes, You Have To Hold It Right.™️

(Pardon me for engaging in a bit of anthropomorphism here. It is incorrect to think of LLMs, bags of floating points masquerading as a slot machine that impersonates a human, as teammates. But, we gender ships and point at little objects and say “look at that cute guy/gal” all the time, so I think there’s precedent in this way of relating to our inventions and environment.)

Agents are a collaborative partner:

- That is available any time…

- …that you’re not over your token spend/quota

- That is often wrong…

- …but takes no offense at being corrected (in fact it’s already cliché how they respond with “you’re absolutely right”)

- Which recently learned software development…

- …at least, the thought process and basic tooling therein

Learning to collaborate with your enthusiastic partner

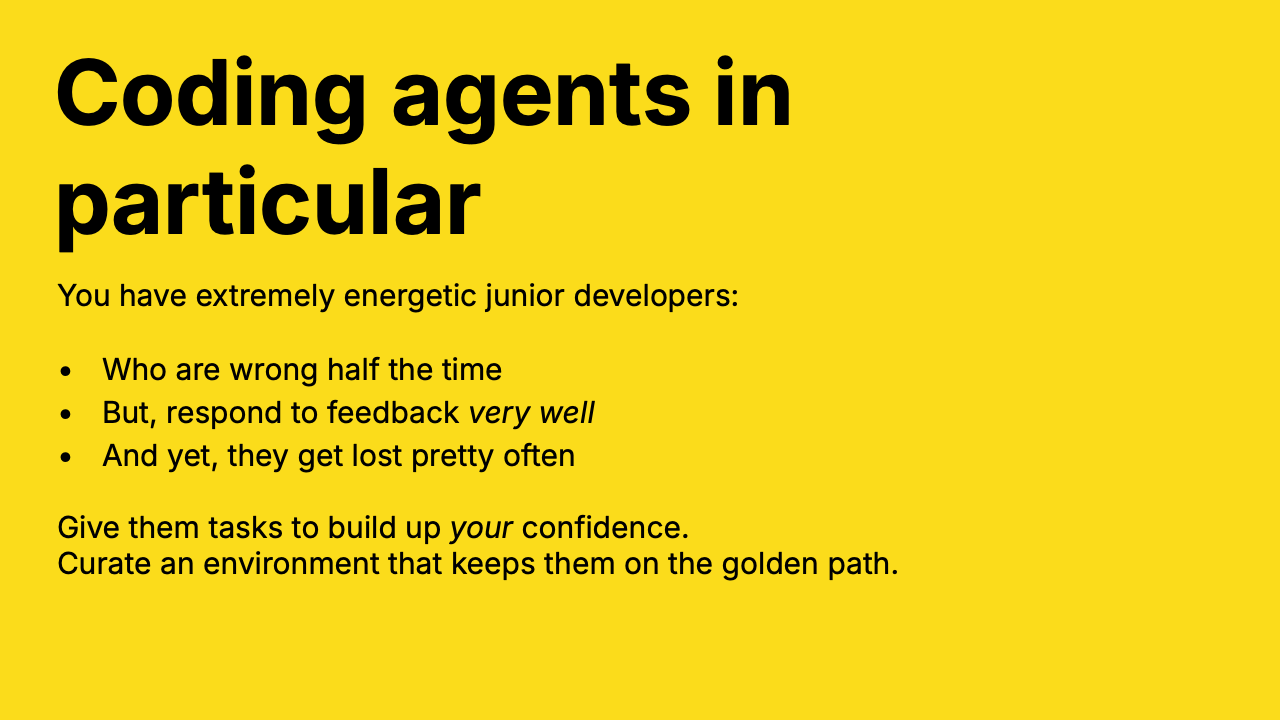

You have extremely energetic junior developers:

- Who are wrong half the time

- But, respond to feedback very well

- And, they get lost pretty often

The way you succeed is:

- Give them tasks to build up your confidence. Just like you would with a junior dev.

- Curate an environment that keeps them on the golden path. Just like you would to onboard new developers, help forgetful team members, automate formatting and idiomatic rule compliance, validate behavior, etc.

That is to say, collaborating with a coding agent is not that different from any other kind of collaboration. Set some guidelines, agree on a goal, build trust, iterate, and challenge each other to reach just a little higher every time.

Goals ✖️ guidelines ✖️feedback

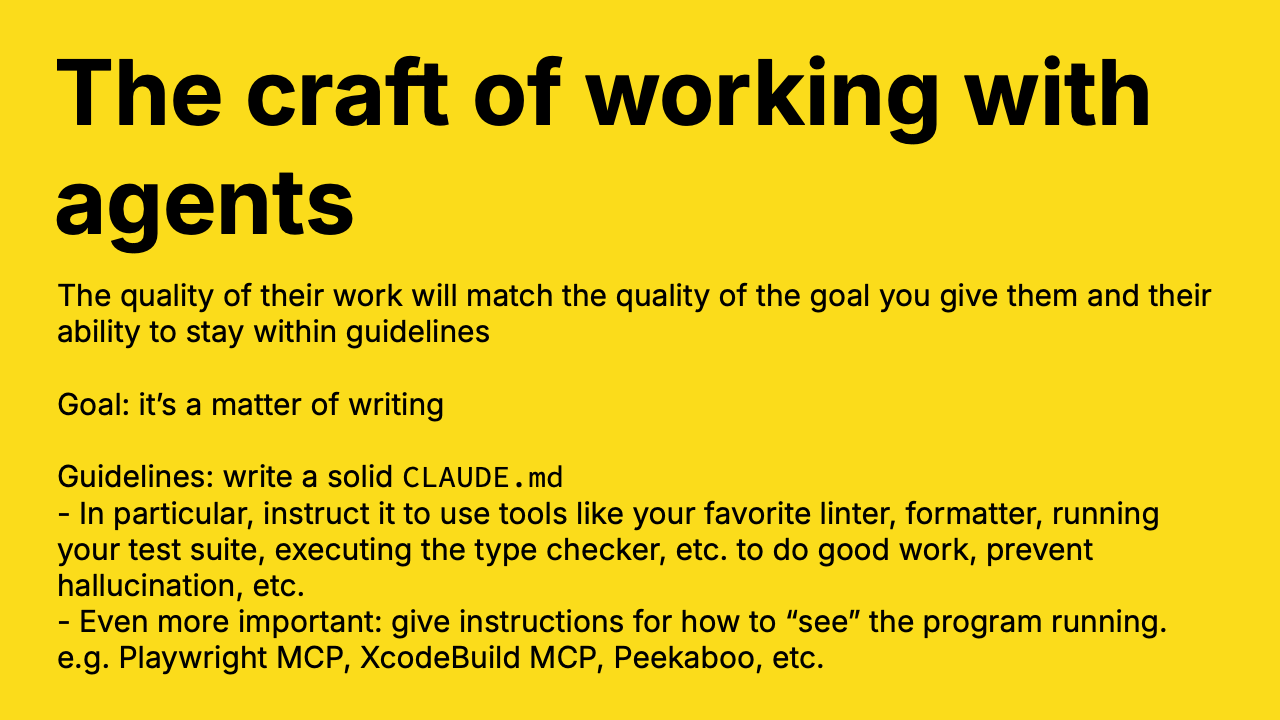

The quality of an agent’s output is proportional to the quality of the goal you give them and their ability to stay within guidelines.

Goals are a matter of writing. I see folks succeeding in two ways:

- Give the agent short, specific goals/prompts. But, encourage them to ask questions (Claude recently added a tool for just this, it works pretty great!) and use their planning mode to get their context window in order before starting.

- Or, give the agent an exhaustive spec, often written with assistance from another “reasoning” model. Tell it to carefully implement one step at a time (lest they exceed their context window and go loopy).

What I’m calling guidelines, most folks call context engineering. Agents have a limited “memory” size (context window, 200K tokens for the good coding models) in which they operate with uncanny ability. They need at least half of that as working space to get the job with some degree of autonomy.

Deciding what to put in the remaining context window is a matter of strong preference. Here’s mine:

- Write a solid

CLAUDE.md. This is the “readme for robots”. Include the most important details about what the project is, how to run it, what the team standards are, and how to “learn more” by reading docs or searching the code. - In particular, instruct your coding agent to use tools like your favorite linter, formatter, running your test suite, executing the type checker, etc. to do good work. These feedback loops are crucial to prevent hallucination and let the agent run autonomously.

- Even more important: give instructions for how to “see” the program running. e.g. Playwright MCP, XcodeBuild MCP, Peekaboo, are important tools here. The longer an agent run its goal-seeking loop in its own, the better. The ability to run the program it’s working on and see if it achieved its goal, without human intervention, is where the uncanny magic really happens.

Delegate the work, specialize in thinking

Things are moving quickly in this space, but I feel confident saying humans in the loop will remain a requirement for the next several months, at least.

Agents forget, sometimes during a session. But you can solve this via CLAUDE.md and adding ‘memories’ to it. Or, tools and MCPs help too. There are even tools (like [bd]) to explicitly outboard the agent’s memory to task lists, not unlike a human might.

Helpfully, Claude Code has a /context command that tells you how much of your context window is in use and by what. Claude has a mechanism for compacting (think defragging your Windows 95 hard drive). When you’re running out of the context window, it’s helpful to know that is happening. These are the times you might have to remind the agent about standards and principles that were loaded way back in the beginning of the session. “Hey, don’t forget, lil friend, that we use K&R style function declarations!”

As with any tool, or human for that matter, the first days and weeks of working together are about building a working relationship and trust in each other. For coding agents, I’ve found that asking questions, then throwing speculative or well-defined tasks, is a good path towards developing a sense of when coding agents are useful and when they often miss the mark.

How should coders code with Claude Code 🥁

Quite a bit has been written about this angle, including your truly. I’ll keep this part short and concise.

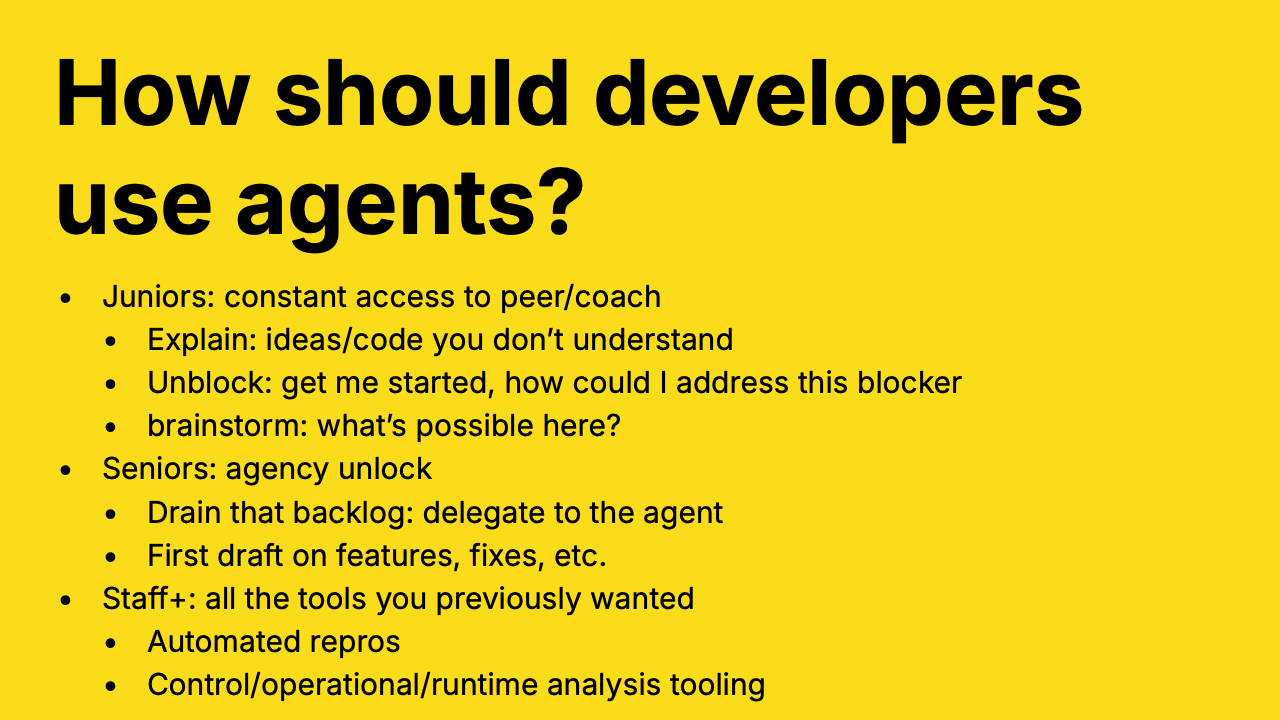

Junior developers (and, as it turns out, experienced developers onboarding with new teams/stacks/systems) can use coding agents as ever-present peers or coaches. Ask the coding agent to explain how something works in the system or what unfamiliar syntax does. If blockers or confusion arise, try to explain the problem and see if the agent can generate useful avenues for troubleshooting your way out. When faced with a project or task which you’re not quite sure how to get started, ask for a few ideas of how you might implement it in this system and pursue the most promising one.

Senior developers should approach coding agents like a speculative productivity unlock. Burn through that backlog of ideas, bugs, and clean-ups. Sometimes the agent will get them right (or, close enough you can tap it in), others it’s a clean miss and it goes back on the stack. Or, you can use it to give you a first draft on features and fixes you’re not quite sure how to approach. Even better: a few first drafts, of which you pick which one to pursue.

Consider: if the time it took you to implement boilerplate and monotonous tasks went to zero, how would you approach getting more of them done?

For staff+ developers, coding agents are an even bigger agency unlock. They can help you brainstorm or tackle automating reproduction of weird, hard to replicate issues. You can build the control, operational, or runtime analysis tooling you’ve always wanted. Again, think about, if the time to build throw-away tools, of increasing complexity, went to zero, what would you do different?

Consider: your relationship to writing code is going to change. Your experience in what works well, where there are hazards, and intuitions on how to get things done are more important than your memorization of APIs and editor shortcuts now. Sorry. 🤷♂️

How should non-coders experiment with Claude Code?

Explore and prune the decision tree. Over years of working closely with product managers, I feel like a lot of it starts with making the best decisions about which potential solutions to customer problems are worth turning into proposals and projects for the software development team.

Consider: If the cost/effort of generating code went down, how would you approach that differently as a product manager or designer?

Turn ideas into prototypes, click around in them, decide if it’s a good idea or not. Work through the backlog of issues that are too small to prioritize but are an irritant nonetheless.

Show me some options. You’ve got a customer problem or feature you want to build, but you’re not sure how to go about it. Ask your agent to give you a few alternatives. I like to specify one should be conservative and one should come out of left field, the weirder the better. Product managers sharing options of how to solve a problem leaves room open for choosing based on scope and effort, rather than throwing us into another estimate, plan, and de-risk exercise.

Work through tedious/combinatory tasks. Rewording jargon in a spec, updating elements of a design system, sizing up how widely used a design token is? Coding agents are great at writing one-off code and scripts to handle tasks like these. Put ‘em to work handling the needful but tedious work you’re avoiding. 😉

In short

Writing is very important! It’s all prompting is. 🙃 Use your words, not too many.

Coding agents are always-on collaborators. Even if they don’t always generate the code of your dreams, they’re valuable for brainstorming and trying out changes with drastically reduced friction.

Give coding agents good goals (prompts), guidelines (CLAUDE/AGENTS.md), and tell them to use tools that keep them on the golden path.

Most of all: experiment! The worst that can happen, nearly, is you’ll write enough to have a clear idea of what you want to accomplish in your product engineering/design/management work but an agent can’t quite get it done. At best, you’ll have a better tool in your belt.

“So then the changes in progress are just there, ready to go.”

“How are they copied? A network sync, an on-disk copy? What about conflict resolution?”

“The data is available on disk and yeah, there’s a sync. Conflicts happen less often than you might think.”

“That’s not how computers work!”

That’s what excitement colliding with worn-in assumptions sounds like.

“So the developer finishes their branch, opens a PR, and then merges it immediately. Once they get feedback, they’ll address it along with whatever they’re working on next. Or a follow-up PR, if they’re working in a different area.”

“But what about foot-guns and project style and crucial but subtle feedback?”

“Yeah, sometimes we shoot ourselves in the foot. But most people only do it a few times before they start to work through it. The upside of getting code into production within minutes instead of hours or days is worth it.”

“You release un-reviewed code within hours of writing it? Multiple times per day? That can’t possibly work!”

Whenever you hear about another team doing something strange that you can’t even process at first, you’re glimpsing a team’s culture peaking through the white space. The more unfathomable or shocking, the deeper the assumption you’re pulling on. Team culture is repetition, that which is done without even thinking about it.

Assumptions seem like an immovable object, until they’re not.

When you hear about practices that rely on none of those habits and assumptions, it brings the whole thing into question. Of course, your initial emotional reactions are “that can’t possibly work” and “why would you even want to do that?”.

Right after “that can’t even” is probably a pretty big insight. If you’re up for it.

Every so often I find myself a few screens deep in an application’s navigation hierarchy and forget I can just pop out instead of going back to the top. I was reading feeds, decided I should do something else, but felt compelled to go back from the item view to the item list to the feed list to the very top of the hierarchy. Silly! I can simply stop reading feeds.

The same thing happens in writing apps: I’m working on a piece and feel like I need to “leave” the app at the very top, seeing all my well-intended but not0-quite-perfect attempts to organize and corral my writing.

I can quit an application from anywhere, not just the top screen!

Algorithmic feeds don’t exhibit this habit, despite presenting very little hierarchy, are worse for this. They actively try to keep comments, liking, sharing, etc. all in one endless view. There’s no “bouncing to the top”, just continual scrolling. Oof.

My habit is probably related to trying to keep as close to zero tabs open at any given time. Which is a great habit!

If we’re pairing or screen sharing, and you reveal a browser window with hundreds of open tabs, rest assured I’m keeping quiet on the outside but encouraging you to close several dozen of those tabs on the inside.

I’m on-board with exploring LLM and agent tooling to improve upon the whole endeavor of software development. But, I consistently find myself disabling Copilot/Claude/etc. completion and next edit prediction in Markdown files. This is the one way in which I’m “too cool” for the machines, the only area where I feel like I certainly know better than the little robot on my shoulder whispering probable next phrases in my ear.

I don’t want any help from the little slot machine of floating-point numbers embedded in my editor. Don’t tell me what I might wanna do or what I could do when it comes to writing, robot! 👴

Writing words, in a text editor, feels like the most creative and think-y activity of the coding regimen. It is a unique situation where I am doing actual invention, creating wholesale of a new cloth, building up from tabla rasa.

Which isn’t to imply that models and agents aren’t helpful for writing, generating ideas, and doing wholesale invention. I love starting with “bad ideas only” and models are superb at that! 😉

When sizing up a stranger, the advice I’ve heard in the past was to observe how they treat service staff: waitstaff, flight attendendants, concierge, etc. This one seems equally appropriate to the internet age:

To rapidly reveal the true character of a person you just met observe them stuck on an abysmally slow internet connection.

— Kevin Kelly, Excellent Advice for Living

If this ain’t a useful frame of reference for our time, I don’t know what is:

Regard for power implies disregard for those without power as is demonstrated by what happened after Moses shifted the route of the Northern State Parkway away from Otto Kahn’s golf course. The map of the Northern State Parkway in Cold Spring Harbor is a map not only of a road but of power—and of what happens to those who, unwittingly, are caught in the path of power.

— Robert A. Caro, The Power Broker

The self-taught amateurs can be weird, or make unorthodox moves that the formally trained can’t see:

“I don’t think it’s very nice,” Angela complained. “I think it’s ugly, but I don’t know anything about modern art. Sometimes I wish Newt would take some lessons, so he could know for sure if he was doing something or not.” “Self-taught, are you?” Julian Castle asked Newt. “Isn’t everybody?” Newt inquired. “Very good answer.” Castle was respectful.

— Kurt Vonnegut, Cat’s Cradle

Case in point: as I was using the revision mode in Ulysses to check this post, nine problems were identified. One misspelling, three incorrect hyphens (another sign o’ the times), and the rest were quibbles about syntax used in the quotes.

Let the experts cook, as it’s said of late.

A little voice in the recesses of my brain, the one that remembers of compiling Linux kernels and collecting WinAmp themes on university Ethernet LANs in the 1990s, is very happy to report that “obscure bit of syntax dot TLD” is still a very valid and fashionable sort of domain name for your programming blog.

Everyone is losing the thread. Maybe that’s what makes this moment in history so difficult to follow and frustrating to live in. Not just politics, and media, and our government(s).

- BMW lost the thread on their sports cars and classic design language.

- Apple lost the thread on great UI.

- JJ Abrams lost the thread on how to (finish) a Star Wars trilogy.

Maybe, somehow, Saturday Night Live only briefly lost the thread because the thread was, almost from the beginning, “did we ever have the thread?”