Personal city guides

I’ve seen lots of sites about how to use software. The Setup and The Sweet Setup are my favorites. You can find lots of sites about how to use ideas like Inbox Zero or Crossfit. People love this stuff.

What I don’t see a lot of is how to use a city, as a visitor or resident. I suspect these things are all around me and I don’t even notice.

A travel guide will tell you where you can go and what you can do, but it won’t tell you how you should go about it. It won’t tell you the little things you’d do as a resident but wouldn’t notice as a traveler. They don’t tell residents (or future residents) what the essence of the city is and what you should do when it’s nice, or gloomy, or when you want to go out, or when you’re hungry.

For example, if I had to write an Austin Setup guide, it would include things like:

- what to eat lots of (tacos and breakfast) and what to eat little of (Italian, oddly enough)

- where to go when it’s nice outside (S. Congress, Auditorium shores, or Zilker park), where to go when it’s blazing hot (Barton Springs), or where to go when it’s miserable outside (one of the many great coffee shops)

- where to find funny people and where to find technology people (because those are my scenes)

The thing is, this would end up reflecting my idioms. Not as useful for someone who wants to do sports, or outdoorsy activities, or music. This thing is more personal, like an interview on The Setup about how people use computers to do their cool thing. Sort of a “how I’ve hacked my city to work better for me” guide. A reverse travel guide of sorts; not for everyone else, just for me.

Universes from which to source test names

A silly bit of friction in writing good tests is coming up with consistent, distinctive names for the models or object you may create. Libraries that generate fake names, like Faker, are fun for this, but they don’t produce consistent results. Thus I end up thinking too hard.

Instead, I like to use names from various fictional-ish universes:

- Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner: Acme Corp, Ajax, Fleet Foot corp. etc. Bonus: read through the extensive laws and rules of this universe!

- Mickey Mouse universe: you can't go wrong with putting Disney trademarks in your code.

- CIA cryptonyms: when I want my teammates to wonder if they know everything going on with our project.

Hopefully my teammates enjoy these little easter eggs as much as I enjoy looking them up when I need something fancier and less dry than metasyntactic variables.

You should practice preparatory refactoring

When your project reaches midlife and tasks start taking noticeably longer, that’s the time to refactor. Not to radically decouple your software or erect onerous boundaries. Refactor to prepare the code for the next feature you’re going to build. Ron Jeffries, Refactoring – Not on the backlog!

Simples! We take the next feature that we are asked to build, and instead of detouring around all the weeds and bushes, we take the time to clear a path through some of them. Maybe we detour around others. We improve the code where we work, and ignore the code where we don't have to work. We get a nice clean path for some of our work. Odds are, we'll visit this place again: that's how software development works.

Check out his drawings, telling the story of a project evolving from a clear lawn to one overwhelmed with brush. Once your project is overwhelmed with code slowing you down, don’t burn it down. Jeffries says we should instead use whatever work is next to do enabling refactorings to make the project work happens.

Locality is such a strong force in software. What I’m changing this week I will probably change next week too. Thus, it’s likely that refactoring will help the next bit of project work. Repeat several times and a new golden path emerges through your software.

Don’t reach for a new master plan when the effort to change your software goes up. Pave the cow paths through whatever work you’re doing!

Sometimes it's okay to interrupt a programmer

I try really hard to avoid interrupting people. Golden rule: if I don’t want interruptions I shouldn’t impose them on other, right? Not entirely so.

Having teammates around, and interrupting them, has saved my butt. I’ve avoided tons of unnecessary work and solving the wrong problems, and that’s just the last week!

Communicating with others is a messy, lossy affair. We send messages, emails, bug reports with tons of partial context and implicit assumption. Not (always) because we lack empathy or want to bury ideas in unstated assumptions, but because we’re in a hurry, multitasking, or stressed out.

When you interrupt a co-worker you can turn five minutes of messages back and forth to thirty seconds of “Did you mean this?” “Yeah I meant that!” “Cool.”

When you interrupt a co-worker you can ask “this made sense but you also mentioned this which didn’t entirely make sense” and they can say “oh yes because here’s the needle in the haystack” and now you can skip straight to working with the needle instead of sifting through the haystack that was your own assumptions wrongly contextualized.

If your coworker is smart, they are keeping track of why people interrupt them. Later they’ll try to make it easier for you to not interrupt them, e.g. write documentation or automate a task. Maybe they want you to interrupt them so that whenever someone wonders “why haven’t we automated this?” they can talk to you about how it’s important to have a human hand on it rather than let failed automation go unnoticed.

There are plenty of reasons not to interrupt someone. I know the struggle. I do my best to respect when people put their head down to concentrate and get stuff done. I always spend a few minutes rereading communications or spelunking the code, logs, or whatever context I have before interrupting someone. It’d be rude to interrupt before I even started trying. But, there’s a moment when the cost and benefit of interrupting someone so I can get something done faster swings towards mutual benefit. That’s when I interrupt them.

Let's not refer to Ruby classes by string

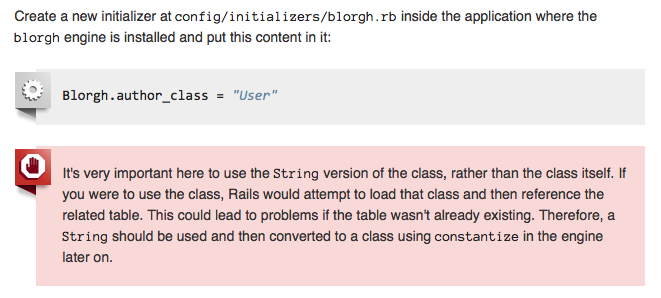

I am basically OK with the tradeoffs involved in using autoloading in Rails. I do, however, rankle a little bit at this bit of advice in the Rails guide to developing engines.

[caption id=“attachment_4216” align=“alignnone” width=“661”] Screencapture from Rails Guide to Engines[/caption]

Screencapture from Rails Guide to Engines[/caption]

In short, when configuring an engine from an initializer, you’re supposed to protect references to autoloaded application classes (e.g. models) by encoding them as strings. Your engine later constantizes the string to a class and everything is back to normal.

A thing I am not OK with is “programming with strings”. As an ideal, strings are inputs from other machines or humans and internal references to code are something else. In Ruby, symbols fill in nicely for the latter. Could I refer to classes as Symbols instead of Strings and live with the tradeoffs?

Well it turns out, oddly enough, that Rails is pretty sparing with Symbol extensions. It has only 120 methods after Rails loads, compared to 257 for String. There are no specific extensions to symbol, particularly for class-ifying them. Even worse (for my purposes), there isn’t a particularly great way to use symbols to refer to namespaced classes (e.g. Foo::Bar).

But, the Rails router has a shorthand for referring to namespaced classes and methods, e.g. foo/bar#baz. It doesn’t bother me at all.

In code I have to work with, if at all possible, I’d rather refer to classes like so:

- Refer to classes by their real ClassName whenever possible given the tradeoffs of autoloading

- When autoloading gets in the way, refer to things by symbols if at all possible

- If symbols aren’t expressive enough, use a shorthand encoded in a string, e.g.

foo/bar#baz - … (alternatives I haven't thought of yet)

- Refer to classes by their full string-y name

But, as ever, tradeoffs.

They're okay political opinions

The downside to the Republicans proposing a healthcare bill is that it’s a major legislative disappointment, given they’ve spent seven years symbolically opposing healthcare. The upside is that, at least, we have something substantive to discuss about healthcare. The silver lining is possibly voters will come to see the Republican party for its cynicism.

What is there to talk about? We could start with David Brooks on how we got to the point wherein the GOP has received their moment in the sun. He argues that neglecting three ideas led us to the propaganda of the Trump era:

First, the crisis of opportunity. People with fewer skills were seeing their wages stagnate, the labor markets evaporate. Second, the crisis of solidarity. The social fabric, especially for those without a college degree, was disintegrating — marriage rates plummeting, opiate abuse rates rising. Third, the crisis of authority. Distrust in major institutions crossed some sort of threshold. People had so lost trust in government, the media, the leadership class in general, that they were willing to abandon truth and decorum and embrace authoritarian thuggery to blow it all up.

Brooks argued Obama should have addressed these crises, which the ACA arguably did for the second. IMO, Republicans stoked all three of these fires while pointing their fingers elsewhere. Supply side economics built the first crisis, privatization the second, and propaganda media the third.

Meanwhile in Congress, Paul Ryan is rolling up his sleeves and saying taking healthcare away from Americans is about giving them freedom. Paul Ryan’s Misguided Sense of Freedom:

...But Mr. Ryan is sure they will come up with something because they know, as he said in a recent tweet, “Freedom is the ability to buy what you want to fit what you need.”He went on to argue that Obamacare abridges this freedom by telling you what to buy. But his first thought offers a meaningful and powerful definition of freedom. Conservatives are typically proponents of negative liberty: the freedom from constraints and impediments. Mr. Ryan formulated a positive liberty: freedom derived from having what it takes to fulfill one’s needs and therefore to direct one’s own life.

(Positive and negative freedom, as terminology, always confuse me; this bit is well written!) This op-ed makes a nice point: healthcare as envisioned by Obamacare, and other more progressive schemes, imagine an America where we are free from worrying about health care. Preventative care happens because we needn’t worry whether we should spend the money elsewhere or take the day off. Major health care events like pregancy or major illness are only intimidating because they are life events, not life-changing unfunded expenditures.

I cannot understand why, outside of deep cynicism of the American dream, Republicans in Congress would not want this kind of free world.

A little PeopleMover 💌

I love the Tomorrowland Transit Authority PeopleMover. It’s what a transportation system should be.

[caption id=“attachment_4190” align=“alignnone” width=“500”] People Mover entrance, overlooking Main Street and the Cinderalla Castle, overlooking Tomorrowland[/caption]

People Mover entrance, overlooking Main Street and the Cinderalla Castle, overlooking Tomorrowland[/caption]

Outside but covered. Elevated so pedestrians can pass below it. Passing in and out of nearby structures. Couch-like.

[caption id=“attachment_4191” align=“alignnone” width=“500”] The People Mover over Test Track and Space Mountain[/caption]

The People Mover over Test Track and Space Mountain[/caption]

Futuristic but achievable. Doesn’t isolate people from each other. You’re one of my favorites, People Mover.

Your product manager could save your day

I thought the feature I’m working on was sunk. An API we integrate with is, let us say kindly, Very Much Not Great. Other vendors provide an API where we can request All The Things and retrieve it page by page. This API was not nearly so great, barely documented, and the example query to do what I needed didn’t even work.

Sunk.

Luckily, only an hour in, I rolled over to the product manager and asked if it was okay if we were a little clever about the feature. We couldn’t request All The Things, but we could request Each of The Things that we knew about. It wasn’t great, but it was better than sunk.

The product manager proceeded to tell me that was okay and in fact that’s kind of how the feature works for other APIs too. I hadn’t noticed this because I was up to my neck in code details. She described how this feature is used in out onboarding process. It wouldn’t matter, at that level, whether we made a dozen requests or a hundred.

I wrote basically no code that day. Someone who “crushes code” or “moves fast and breaks things” would say I didn’t pull my weight. Screw ‘em.

I didn’t go down a rabbit hole valiantly trying to figure out how to make a sub-par API work better. I didn’t invent some other way for this feature to work. My wheels were spinning, but only for a moment.

Instead, I worked with the team, learned about the product, brainstormed, and figured out a good way forward. I call it a very productive day.

Three Nice Qualities

One of my friends has been working on a sort of community software for several years now. Uniquely, this software, Uncommon, is designed to avoid invading and obstructing your life. From speaking with my Brian, it sounds like people often mistake this community for a forum or a social media group. That’s natural; we often understand new things by comparing or reducing them to old things we already understand.

The real Quality Uncommon is trying to embody is that of a small dinner party. How do people interact in these small social settings? How can software provide constructive social norms like you’d naturally observe in that setting?

I’m currently reading How Buildings Learn (also a video series). It’s about architecture, building design, fancy buildings, un-fancy buildings, pretty buildings, ugly buildings, etc. Mostly it’s about how buildings are suited for their occupants or not and whether those buildings can change over time to accommodate the current or future occupants. The main through-lines of the book are 1) function dictates form and 2) function is learned over time, not specified.

A building that embodies the Quality described by How Buildings Learn uses learning and change over time to become better. A building with the Quality answers 1) How does one design a building such that it can allow change over time while meeting the needs and wants of the customer paying for its current construction? and 2) How can the building learn about the functions its occupants need over time so that it changes at a lower cost than tearing it down and starting a new building?

Bret Victor has bigger ideas for computing. He seeks to design systems that help us explore and reason on big problems. Rather than using computers as blunt tools for doing the busy work of our day-to-day jobs as we currently do, we should build systems that help all of us think creatively at a higher level than we currently do.

Software that embodies that Quality is less like a screen and input device and more like a working library. Information you need, in the form of books and videos, line the walls. Where there are no books, there are whiteboards for brainstorming, sharing ideas, and keeping track of things. In the center of the room are wide, spacious desks; you can sit down to focus on working something through or stand and shuffle papers around to try and organize a problem such that an insight reveals itself. You don’t work at the computer, you work amongst the information.

They’re all good qualities. Let’s build ‘em all.

I have become an accomplished typist

Over the years, many hours in front of a computer have afforded me the gift of keyboarding skills. I’ve put in the Gladwellian ten thousand hours of work and it’s really paid off. I type fairly quickly, somewhat precisely, and often loudly.

Pursuant to this great talent, I’ve optimized my computer to have everything at-hand when I’m typing. I don’t religiously avoid the mouse. I do seek more ways to use the keyboard to get stuff done quickly and with ease. Thanks to tools like Alfred and Hammerspoon, I’ve acheived that.

With the greatest apologies to Bruce Springsteen:

Well I got this keyboard and I learned how to make it talk

Like every good documentary on accomplished performers, there’s a dark side to this keyboard computering talent I posess. There are downsides to my keyboard-centric lifestyle:

- I sometimes find it difficult to step back and think. Rather than take my hands off the keyboard, I could more easily switch to some other app. I feel like this means I'm still making progress, in the moment, but really I'm distracting myself.

- Even when I don't need to step back and think, it's easy for me to switch over to another app and distract myself with social media, team chat, etc.

- Being really, really good at keyboarding is almost contrary to Bret Victor's notion of using computers as tools for thinking rather than self-contained all-doing virtual workspaces.

- Thus I often find I need to push the keyboard away from me, roll my chair back, and think, read, or write to do the deep thinking.

All that said, when I am in the zone, my fingers dance over this keyboard, I think with my fingers, and it’s great.

The occurrence and challenge of ActiveRecord lookup tables

I’ve noticed lots of Rails apps end up with database-backed lookup tables. Particularly in systems with some kind of customer or subscription management, it’s almost guaranteed that User or Customer models belong_to SubscriptionLevel or Plan models. Thus, you frequently need to query both models.

If you’re looking for avoidable database work, as I sometimes have, this seems like low-hanging fruit. Plan level models very rarely change. You could replace those Plan or SubscriptionLevel models with a hardcoded data object and move on.

In my experience, you now have a white whale on your hands. This low-hanging fruit may haunt you for a while. It could cause you to invent increasingly implausible mechanisms for ridding yourself of this “technical debt” (scare quotes, it’s a trade-off and not actual technical debt). Teammates will appear drowsy when you mention this problem and its technical details, then back away slowly.

Why is it so tricky to convert AR database lookups to non-AR in-memory lookups?

I’ve attempted this twice. Both times, I tried to grab as little surface area as possible and ended up with nearly all of the models. A current teammate is trying now and suffering a somewhat similar fate. They’re more detail-oriented and motivated than I am, so I hope they’ll succeed. (Ed. they succeeded!)

Is this phenomenon something we can easily write off to coupling or is it something else? My pessimistic, gossip-y sense leads me to think people who have become ORM Skeptic went down this path thinking it’s inevitable if you accept an ORM into your life. They came away a dark shade of who they were with the conclusion that ORMs ruin everything. However, the phases of coping that involve a three thousand word essay and then writing a new database layer thing don’t actually solve this problem.

In the ActiveRecord flavor of ORMs, it is easy to describe model graphs and interactions amongst those graphs. Once you’ve got the whole model graph, its often difficult to isolate a subsection of it. AR, in particular, can make it easy to violate Demeter and reach through that graph in hard-to-refactor ways.

Our lack of great and general tools for working with Ruby code that uses these graphs and rewriting said code is another big challenge. Solving these problems requires visualizing the direct and transitive connections between models. Then you need some kind of refactoring tool to rewrite code to use an indirection object instead of directly coupling. We lack both of those in the Ruby world.

Optimistically, I’d think this is a case of refactoring smarter. Given a solid test suite you could:

- connect your lookup models to an in-memory SQLite database populated at app start, no need to remove ActiveRecord

- use one of the several libraries that implement enough of the ActiveRecord interface to replace models with classes backed by static data

- lots of things I haven't thought or heard of!

The thing you wouldn’t want to do, and where I faltered at least once, was to let it become a long-running task. When you’re making changes all over the code base, any amount of churn behind your back is potentially crippling. If you can freeze the code base, I highly recommend it. (Coincidentally, this is exactly what my smarter-than-me teammate did!)

The other thing to keep in mind is that, inevitably, you will come across weird uses of ActiveRecord and Rails that you didn’t know about, are pretty sure you don’t like, and have to work with anyway. Set aside time for these known unknowns.

When dealing with potentially large, radical changes to your application code, how radical are you willing to go to make many smaller changes than one big one? There’s no crisp answer here. All code grows awkward in different ways. As always: divide, conquer, and celebrate your victories!

The annoying browser boundaries

Since I started writing web applications in around 1999, there’s been an ever-present boundary around what you can do in a browser. As browsers have improved, we have a new line in the sand. They’re more enabling now, but equally annoying.

Applications running on servers in a datacenter (Ruby, Python, PHP) can’t:

- interact with a user’s data (for largely good reason)

- make interesting graphics

- hop over to a user’s computer(s) without tremendous effort (i.e. people running and securing their own servers)

Browser applications can’t:

- store data on the user’s computer in useful quantities (this recently became less true, but isn’t widely used yet)

- compute very hard; you can’t run the latest games or intense math within a browser

- hang around on a user’s computer; browsers are a sandbox of their own, built around ephemeral information retrieval and not long-term functionality

- present themselves for discovery in various vendor app stores (iTunes, Play, Steam, etc.)

It may seem like native applications are the way to go. They can do all the things browsers cannot. But!

- native apps are more susceptible to the changing needs of their operating system host, may go stale (look outdated) or outright not work anymore after several years

- often struggle to find a sustainable mechanism for exchanging a user’s money for a developer’s time; part of that is the royalty model paid to platforms and stores, part of that is the difficulty of business inherent to building any application

- cannot exceed the resources of one user’s computer, except for a few very high-end professional media production applications

In practice, this means there’s a step before building an application where I figure out where some functionality lives. “This needs to think real hard, it goes on a very specific kind of server. This needs to store some data so it has to go on that other server. That needs to present the data to the user, so I have to bridge the server and browser. But we’d really like to put this in app stores soooo, how are we going to get something resembling a native app without putting a lot of extra effort into it?”

There’s entirely good reasons that this dichotomy has emerged, but it’s kinda dumb too. In other words, paraphrasing Churchill:

Browsers are the worst form of cross-platform development, except for all the others.

Just tackle the problem

There’s a moment when a programming problem engulfs me. Perhaps it’s exciting and intriguing, maybe it’s weird and infuriating, maybe it’s close to a deadline and stressing me out. Whichever it is, I’m not so great at managing that intensity.

I can’t handle adult responsibilities. Any external demands on my time are met with impatience. My thoughts drift to the problem when I’m not otherwise occupied. I get on my own case about why it’s not solved, festering a negative feedback loop of feeling bad about not having solved it yet and then feeling worse about not having solved it yet.

I am able to step away from it a little bit. Go grab food, spend some limited time with my wife or dogs. It doesn’t fully engulf me. But I can’t detach myself from it.

It’s not frustrating that I get excited or perturbed by my programming work. It’s frustrating that I let it stress me out, to negatively effect my life even if only for a short time. Especially that it’s spurious, that I don’t need to stress out over it. My code’s not going to endanger lives, yet.

The best coping tactic I’ve come up with, so far, is to tackle the problem. Don’t go stew on the circumstances of the problem. Maybe take that moment away to pet a dog and release some stress. Then, find a solution that fits the time and context of the problem so I can get back to thinking clearly about work and life.

Sometimes, I get lucky and the solution to the problem presents itself.

What is the future of loving cars?

To me, a great car is equal part shape, technology, sound, and history. It seems like the future of cars is all technology at the expertise of all other factors. What will it mean to love cars over the next ten years?

A well shaped car is defined by function. A long hood accommodates an engine running the length of the car and not between the wheels. Aerodynamic surfaces, not too many please, keep the car pressed to the road. The shape of the car is further of a function of air inlets to cool all the moving parts. Once all that is done, you can think of the form, getting just the right balance of smooth curves and straight lines.

Future cars are likely to move toward aerolumps. Drag is always the enemy of cars, doubly so for anything seeking efficiency. But the form needed to accommodate moving parts (read: combutions engines and their support infrastructure) will go away. You’re left with just a bubble holding the passengers. Not inspiring.

The sound of future cars is the sound of air running over the car and tires meeting the road. You may hear the occassional whine of an electric motor, perhaps an artifical soundtrack inspired by old combustion engines. No more growls, burps, and high-rev screams.

When all this sorts out, some companies will have a more interesting product due to their use of technology. A lot of companies will have a more boring but practical product. We will surely say, “they don’t make them like they used to” because literally, of course, they won’t.

But what will we find to love about how cars are built and function? Will that fade as a historical note while we revel in the agency a personal car brings without some of the external costs of highways, parking lots, and petrofuels?

Levels of musical genius

I often think about what kind of unique musical talent some performer I enjoy possesses. A few examples:

- J-Dilla was at the center of many groups doing amazing things creating an exciting moment in time, but at the same time was a master composer himself

- Prince or Quincy Jones were often running multiple performers and groups, serving as sort of the well from which their respective musical ideas came from

- Tom Petty isn't particularly gifted technically and doesn't write ground-breaking songs but is very, very good at working within a specific form and genre, one of the best in that space

- Jimmy Page is not musically the best or most innovative, but very adept at the style he created for himself, is technically a good guitarist

- Pete Townsend holds a group together, is the glue that leads a group of virtuosos, somehow the master creator and craftsperson who runs the group with a solid hand without making it all about him

- Brian Wilson plays a whole ensemble, a studio as an instrument, micromanaging every detail to produce a sublime musical whole; Bruce Springsteen is close to this

- Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen are excellent wordsmiths who get great results when the music around them is also pretty good

- Annie Clark is a guitar-shred-meister who runs with the avant-alt mantle set forth by The Talking Heads

- Merrill Garbus builds amazing lo-fi layered music of incredible stylistic range that sounds right at home on the festival circuit

The connection amongst these individuals is more than playing their instruments or writing their songs. They’re working a level above that, whether it’s Tom Petty and Jimmy Page making fine-tuned rock or J-Dilla, Prince, and Merrill Garbus micromanaging a subgenre into existence. I’m a little envious of that level of musical acumen.

Four parks, one day

In January, Courtney and I went to Disney World for her birthday. We bought an annual pass last year, so we’ve literally been a few times over the past year. This time ‘round, Courney wanted to visit all four parks in one day. Our Official Rules were we had to ride two rides (or see a show and do a ride), drink a boozy drink, and eat a dessert in each park. We made it!

We had a few other days to enjoy the park at a more leisurely pace. We did a Safari tour at the Animal Kingdom resort, which afforded opportunities for giraffe selfies. I got to take lots of pictures and enjoy Epcot and Tomorrowland, my favorites. Along the way, we ate a bunch of ice cream and sang along with “Let It Go” nearly every day.

As ever, a magical time.

[gallery ids=“4040,4041,4042,4043,4044,4045,4046,4047,4048,4049,4050,4051,4052,4053,4054,4055,4056,4057,4058,4059,4060,4061” type=“rectangular”]

Protect the beginner's mind

Someone joins your team. They have a beginner’s mind about your project and culture.

Take a person with beginner’s mind, tell them about how things have always been, how they got that way, and insist we just try to keep that status quo? That’s a shame.

When you harness a beginner’s mind, you have a short window to make the most of their new perspective. After a while, it becomes the team or culture’s perspective. Opportunity lost.

Put a person with beginner’s mind in a room with someone who knows All the Reasons. If they survive, you have just created a ton of learning for both people.

Protect the beginner’s mind. Listen to it. Act on it.

The right way and the practical way

Brent Simmons, Reason Number 33,483 to Hate Programming:

Or I could have the superclass expose the appIsTerminating property in its header file, so that the subclass could see it. This also sucks, because a controller class has no business exposing its own copy of global application state.

In the end, though, that’s what I did. (Along with a comment that the property was there for subclasses.)

It reminds me that there are two competing values:

Do everything the right way every time.

Make responsible and professional decisions about time and expenses and benefits and drawbacks.

My nature is to take path #1. It is so hard for me to take path #2. I have the utmost respect who can work on sprawling, modern software and stay on path #2. But path #1, always pulling me in and sending me down rabbit holes.

Sometimes I wonder which of these paths got me to where I am in my career. Others, I wonder if I think I’m a everything-the-right-way person but really I’m a responsible-and-professional-tradeoffs person.

A brain’s a weird place to live.

Contrast NYC and SF

Dallas and Austin are the cities I’ve spent my life in. I’ve spent maybe three weeks of my life, total, in San Francisco and New York City. They’re similar in that SF and NYC are both a Whole Other Thing in comparison to my Texan expectations. Indeed, they’re global cities operating at an entirely different order of magnitude.

It’s long puzzled me why I find NYC less intimidating and strange than SF. I’m starting to think its the attitudes. Walking through either town, I frequently suspect that I’m Doing It Wrong, from where to eat to where to sleep to how to use the subway.

In NYC, I suspect the natives are looking on as I struggle to hail a cab or catch a train, but they are silent in their snickering about me doing it wrong.

SF feels much more in your face, eager to tell you “You have done it wrong and you should feel bad”, from the subway systems to the tech bubble.

San Francisco very much remains a frontier town. You move there to make your fortune, to burn bright and “compress your career into several years”. It’s at the same time fractured by law (the city has three different transit systems, all using different tokens last time I visited) and lawless (Uber and Airbnb in particular are about landgrabs before the law can catch up with technology). It’s at once a global city and embarrassingly self-centered.

In summary, I guess I just like Texas a lot better. Even after our awful lawmakers.

Framework and Library people

By unscientific survey, I think many developers would prefer to work in a “framework world” where many decisions of principle and organization are passed down by a vendor or architecture team. Think Rails/Django/Laravel for backends, Ember/Elm for frontends, Unity for games. These are the Framework people.

Fewer developers would prefer to create their own world, building up tools and libraries to suit. They select a few first principles and build their own world. They’re the bebop jazz musician, eschewing big band gigs and music people can dance to to create their own intellectual world. These are the Library people.

I’m a Framework person. The allure of Library people sometimes tempts me after I look at a beautifully-restored car or a well-structured song. But constructing a library world is thankless and not particularly high leverage, unless you succeed in creating something for framework people. Weird, eh?