Its never a bad time to educate the kids about their rock and roll heritage

Speaking of rowdy Springsteen: found this anachronistic and slightly surprising performance of “Ramrod" from the 2002 MTV Video Music Awards.

Presumably he was out promoting The Rising, a sincere collection of 9/11 songs. Nonetheless, I guess he decided it was a good time to educate the kids about their rock and roll heritage.

"Maximum theoretical sincerity"

Pitchfork: Talking Head: Remain in Light

By 1980, the conflict in music between what was thought and what was felt was in full cry. As disco continued to monopolize music you could dance to, rock reached a point of maximum theoretical sincerity. Pink Floyd’s The Wall, possibly the least ironic recording of all time, was the No. 1 album in America for 15 weeks. It was finally unseated by Bob Seger’s Against the Wind, which was knocked out of the top spot by Billy Joel’s Glass Houses. Ostensibly, these were works of deep sentiment. To a generation of punks, though, they were rock at its most bloodless and calculating. … The central insight of Talking Heads—what made them not just weird but exciting and relevant—was that their art-house affectation felt more sincere than a lot of American culture.

Completely unrelated but somewhat adjacent: the unseen magic trick Bruce Springsteen pulls off, for me, is to thread the needle between sincere storytelling, grandiose maximalism, and bar band raucousness.

Without Afrobeat, though, there is no Remain in Light. The central role of West-African polyrhythms in the album’s sound draws attention to a curious aspect of its longevity. Could a group of white musicians playing Afrobeat be taken sincerely in 2018? Virtually every genre of American music, including punk and especially rock, is taken from black forms. Afrobeat is not African-American, though; it’s straight-up African. The 21st-century sensibility finds something problematic in a band of white art-school types playing West African music. Earlier this year, the Beninese musician Angelique Kidjo released her own version of Remain in Light, which NPR described as “an authentic Afrobeat record” compared to the original. Given how closely Kidjo followed the Talking Heads’ arrangements, this description raises questions about what we mean when we say “authentic.”

This is a great review and a pretty good read.

Elvis Costello is a jewel unstuck in time, simultaneously timeless and of his time. His most recent album, no exception. pitchfork.com/reviews/a…

Wherein writing the dang memo is the easy part

Seth Godin, Get your memo read:

The unanticipated but important memo has a difficult road. It will likely be ignored.

I find this is one of the unexpected challenges of taking on engineering leadership responsibilities. First off, you have to do all the writing things right: use a clear and concise subject, say all the important things up front (probably in bullets!), and develop the important details in thoughtful prose. Even if you nail it there, some people just won’t read, retain, and/or care about the information you have conveyed to them.

Hence: Always Be Repeating Yourself. Always.

Context buckets

Sometimes I ask myself: why did past Adam think this text/link/picture/etc. was important. Increasingly the answer is: put it in a bucket that makes the answer self-explanatory. For example: I have tags in Bear for music, recommendations, notes on The System of the World, Technology, software, Disney, and even for random tweets that I will sometime want to share with someone as proof that I’m not just making this up.

95% endorsed! The exception: I am extremely picky about the size and aspect ratio of windows in relation to how the particular application is designed. I can neither walk into Mordor or simply resize an application to use exactly 50% of my screen.

Pick prolific: quantity, quality, and Chidi's Dilemma

Prolific is better than perfect, Jared Dees:

“Perfect” is a mirage that no one knows how to reach.

I’m fond of restating this in terms of the quantity/quality trade-off. It’s easy for me to fall into the temptation of creating one essay/pull request/turn-of-phrase that exhibits all of the quality that should exemplify my work. But it’s better for me to create a bunch of things that exhibit some of that quality so I can better learn what is essential to the quality and what is illusory.

To borrow Dees’ model: if I write fifty-two blog posts in a year, several of them will be Not That Great. But after the first dozen or so, I’ll start to figure out what’s important in a story and what I thought was important but doesn’t really matter much. This is quantity creating quality; not a tradeoff!

The flip side is Chidi’s dilemma: spending your whole life trying to write every single thing about your area of expertise, with nuance, and producing something so impenetrable that not even a demigod can make sense of it.

In short: quantity doesn’t reduce quality. Quantity is the feedback loop that creates Quality.

We are now a two robot vacuum family! One for the cats upstairs, one for the dogs downstairs. Courtney loves them both.

The cats and dogs are way smarter than the robots, which just bump around like embodiments of the old Windows logo screensaver. Our floors have never been slightly cleaner and our power strips never in greater threat.

I highly recommend it if you have the means.

It is I, who dwells at coffee shops, who sometimes reads paper books instead of a glass display, who prefers Apple Pay over card swiping when possible.

How I focus more and worry less about the internet

As a long time Rands fan, I highly recommend you partake of the Rands Information Practices and Rands Slack Protocol. Allow me to add some of my favorite tactics.

Get your browser tab situation under control; I get itchy when I have more than several tabs open! (But if you’re the sort who never has less than a few dozen tabs open, I still like you.) Move your most important and favorite blogs and websites into a feedreader. I like Newsblur plus Reeder macOS/Reeder iOS. You can even put Twitters and email subscriptions into Newsblur, which is some next level distraction management.

Learn the keyboard shortcuts. All of them. Dazzle people with your ability to dance across the keyboard and make computers do things. Bonus tip: picking up a mechanical keyboard will make you sound extra amazing but slightly annoy the people who sit close to you.

Customize your system to remove distractions, allow you to focus, reduce drag, and move faster. If other people sit down at your computer and can’t operate it, that’s okay. But, don’t customize it too much. I want to get stuff done, not produce the ultimate hot rod computer for hot rodding computers.

Speaking of hot rodding, do not go too deep on productivity systems. I need a notebook-like app to think in and write stuff down. I need some kind of souped up todo list. Not much else. They are outboard brains, augmenting my ability to function as an adult and as someone thinking about and/or making things. Its tempting to read about everyone else’s Extremely Awesome Productivity Setup, but they’re doing different stuff and have different responsibilities; it’s entertainment, not education.

I cannot read the entire internet. Get really good at guessing whether something that comes across your desk is going to better your understanding of the world. Skip all the clickbait and tribal rage stuff. I look for stuff that provides insight into how we got here or what the future might look like.

That said, don’t accidentally filter your dear friends out in the process of managing the information onslaught. Put them in a special list or feed folder and look at it daily. Engage with them like its 2008 and the internet is still a promising thing that connects us to our friends.

Finally, I highly recommend you follow Rands’ best bit of advice, which is curiously tucked into the last footnote: replace screens by your bed (as many as possible, at least) with a book.

On decision tables and conditionals

Over the years, I’ve heard a few times about something like Decision Tables (Hillel Wayne):

A decision table is a means of concisely representing branching and conditional computations. In the most basic form, you have some columns that represent the “inputs” as booleans and some columns that represent outputs and effects.

It was usually some variation of teams using something like a truth table to define the logic of their application without using a mess of conditionals. It also turned out that there was a compiler optimization where these tables could be laid out such that figuring out which behavior was appropriate to all the inputs was faster than conditionals would have been.

Wayne doesn’t mention anything like this. But, there is mention of using decision tables with an RSpec macro to verify code behavior with less boilerplate assertion logic. So that’s neat!

If I had to sum up my style of coding, I’d say probably a third of it is about reducing the time I spend reading or writing conditional code. That’s where most of the bugs and frustration are. Pushing them down into the compiler, runtime, or database is a fun exercise too.

My favorite question is “why?”

At some point in elementary or junior high school, we were taught all our essays should answer one of five questions: who, what, where, why, or how. These were, at the time, “the five W’s” of writing.

Why is my favorite because it provides context. Asking why usually gets me to the bottom of the situation. It often encapsulates the who/what/where/how/when. It’s the most open ended, which is probably the best part. Asking why almost always makes the next most important question obvious.

I still like the other ones too. When often yields interesting histories or chronologies. Who can lead to a nice bit of biographical or character background. How is great when I care most about progress over deep context. Where can give me a little bit of backstory about why a certain location or geography is important.

Asking why wraps up all of those. Why are shipping containers a standard size? Who decided it should be that way. How did that drastically change global shipping? When did this occur and what changes can we observe from it?

One word, one question. So much to learn!

The systemic sublime makes our world more legible

My new favorite category on Kottke.org is the systemic sublime, wherein our networked, often inscrutable world is made more legible. The connections between ideas and and their instantiations are not always obvious. The history, and often the path dependence, of how we got here make it a little easier to understand our world.

Other fine purveyors of system sublime include Alexis Madrigal, Matt Webb, Tom Armitage, Ribbonfarm, Steven Johnson, and Michael Lewis. My favorite thing about these authors is, they are answering “why?” by connecting the dots between “how”, “who”, and “what”. It’s my favorite kind of thinking!

Advocacy = empathy + speaking to someone else’s conceptual framework. When I’m trying to convey an idea from my head to someone else’s head, the biggest challenge is converting from my conceptual framework and values to theirs. Hence, The words that work:

For example, one partner in a conversation might use concepts like power and tradition and authority to make a case, while the other might rely on science, statistics or fairness. One person might argue with tons of emotional insight, while someone else might bring up studies and peer reviews.

Rare is the success of advocacy that doesn’t involve a lot of empathy, understanding your conversation partner, and letting go of the little details to reach a new local maximum of mutual understanding.

It's dangerous to go alone, take dotfiles

Yesterday I was handed a fresh, nifty new laptop. This is, for me, mildly terrifying. Last time I did a clean operating system install was seven years ago. I’ve carried an idiomatic mixtape of dotfiles, macOS preferences, files, and cruft with me on my personal laptop ever since.

A brand-new, stock laptop is a shock to my highly acclimated and particular system.

I started contemplating how exactly I could get setup relatively quickly. At the same time, I want to pay down a little bit of automation debt. By the next time I’m faced with this situation (when I buy my own computer, if a disk is struck by lightning, etc.) I shouldn’t feel so much like a deer in headlights.

At first I thought I’d attempt to transmogrify my current lightsaber into something like Gina Tripani’s dotfiles. I like how this is structured, and that the initial setup of apps and Unix-y things is bootstrapped by Homebrew. But, then I remembered Thoughtbot’s laptop and dotfiles and convinced myself this was the way to go.

Indeed, laptop helped me cut the Gordian knot of setting up my new machine so I can write code and feel at home on it. I highly recommend it if you have the means.

New dotfile repo forthcoming!

I’m starting a new job tomorrow. I decided to take a week off in-between jobs, mostly to make a quick trip to Disney Land.

I hid most social media apps away, stopped paying attention to news, and caught up on reading. I gave myself a 3-day weekend before our trip to decompress, we went to Disney Land for 3 days, and had a 3-day weekend to relax before I start the next thing. I’ve done a fair bit of writing, watching movies, tinkering with Ableton, and playing games too. A great vacation sandwiched between two stay-cations, in the lexicon of our times.

My mind feels like it’s had a chance to reset and get back to a neutral state. I’m hoping this will help me keep my frame-of-mind looking forward as I start the next job. This was a great decision and I highly recommend you do something like this (granted, Disney Land isn’t everyone’s thing) yourself, if you have the means.

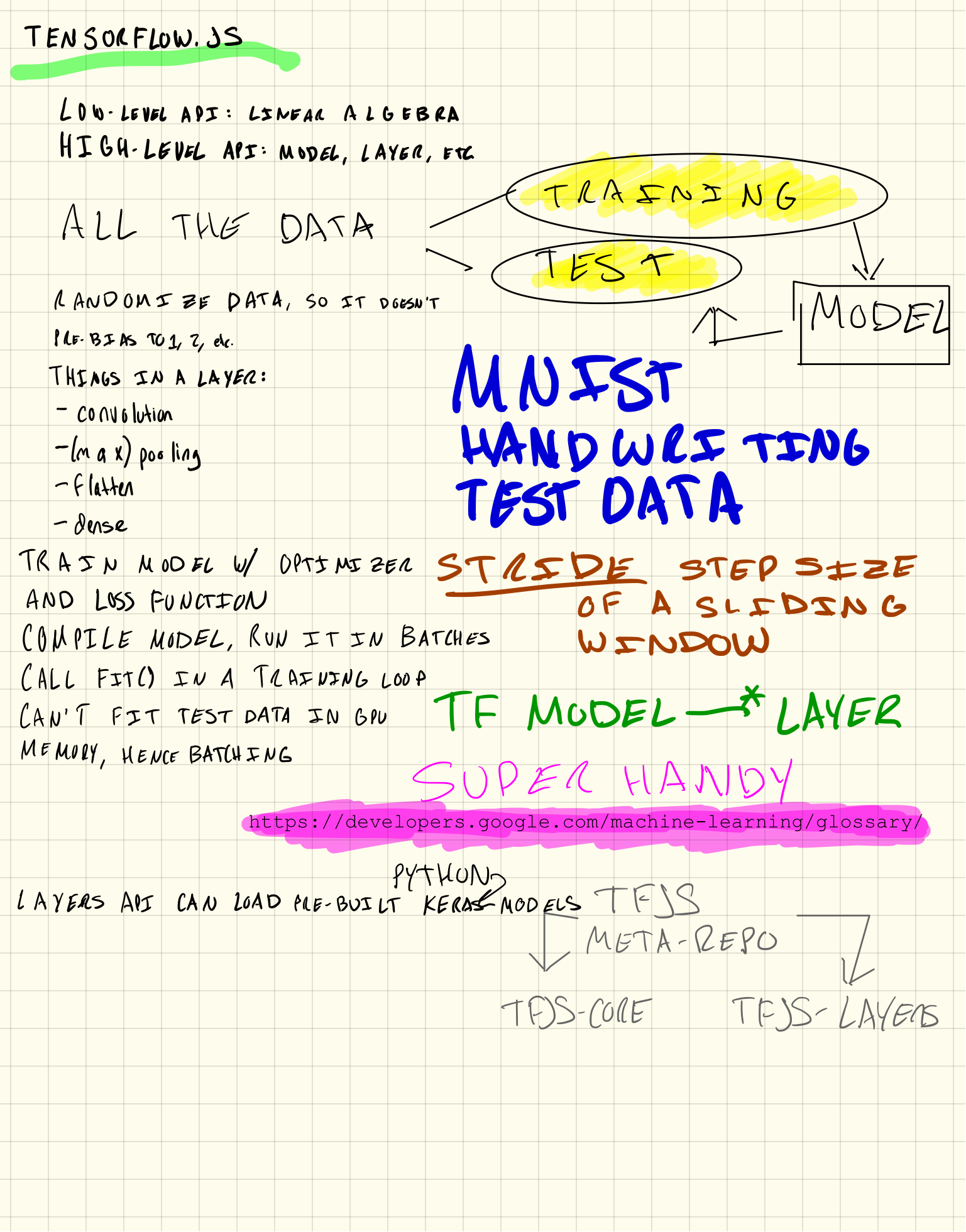

Scribbling through TensorFlow.js

I’ve been trying to wrap my head around machine learning lately. Today I worked through the TensorFlow.js tutorial on recognizing handwritten numbers with a neural network. Herein, my notes and scribbles.

[caption id=“attachment_4714” align=“alignnone” width=“1537”] TensorFlow: it’s about turning linear algebra into models built of layers built of math[/caption]

TensorFlow: it’s about turning linear algebra into models built of layers built of math[/caption]

My previous forays into machine learning left me a little frustrated: I could tell there was language, pattern, and notations to this, but I couldn’t see them from the novelty of new-to-me words like sigmoids, convolution, and hidden layers. Turns out those are part of the language.

But the really handy idioms are encoded in TensorFlow’s high-level model-and-layer API. A model encapsulates a chunk of machine learning that can be trained to classify inputs (images, texts, etc.) based on a mess of training data (pre-classified stuff). Every model is built from a network of layers; layers use linear algebra to transform numbers into classifications.

Once you’ve built a model, you feed it a bunch of training data so that it can learn the coefficients and other number-stuff that goes inside the math-y network. You also provide it with an optimizer and loss function so that as the model is trained, it can know whether its getting better or worse at classifying data.

A really cool thing is you run this training process on your computer’s GPU. GPUs, like machine learning models, are big networks of fast math-y stuff. Beautiful symmetry! On the other hand, you usually can’t fit your training data set into GPU memory, so you end up batching your test data and submitting it to the GPU in loops.

Once all this runs, you’ve got a trained model that can take image inputs (in this case, hand-written digits) and classify them to decimal numbers (0-9). Magic!

Code minutiae, October 23, 2017

For some reason, identifier schemes that are global unique, coordination-free, somewhat humanely-representable, and efficiently indexed by databases are a thing I really like. Universally Unique Lexicographically Sortable Identifier (ulid, for humans) is one of those things. Implementations available for dozens of languages! They look like this: 01ARZ3NDEKTSV4RRFFQ69G5FAV.

Paul Ford’s website is twenty years old. For maybe half that time I’ve been extremely jealous of how well he writes about technology without being dry and technical. When I grow up, I’ll write like that!

How Awesome Engineers Ask For Help. So much good stuff there, I can’t quote it. There’s something in there for new and experienced engineers alike. In particular: don’t give up, actively participate in the process of getting unstuck, take and share notes, give thanks afterwards.

The best time to work on your dotfiles is on weekends between high-intensity project pushes at work. No better time to do some lateral thinking and improving of your workflow. Feels good, man.

You must be this tall to ride the services

If I were trying to convince myself to extract a (micro)service, today, I’d do it like this. First I’d have a conversation with myself:

- you are making tactical changes slightly easier at the expense of making strategic changes quite hard; is that really the trade-off you're after?

- you must have the operational acumen to provision and deploy new services in less than a week

- you must have the operational acumen to instrument, monitor, and debug how your applications interact with each other over unreliable datacenter networks

- you must have the design and refactoring acumen to patiently encapsulate the service you want to build inside your current application until you get the boundaries just right and only then does it make sense to start thinking about pulling a service out

I would reflect upon how most of the required acumen is operational and wonder if I’m trying to solve a design problem with operational complexity. If I still thought that operational complexity was worthwhile, I’d then reflect upon how close the code in question was to the necessary design. If it wasn’t, I would again kick the can down the road; if I can’t refactor the code when it’s objects and methods, there’s little hope I can refactor it once its spread across two codebases and interacting via network calls as API endpoints, clients, data formats, etc.

If, upon all that reflection, I was sure in my heart that I was ready to extract a service, it’d go something like this:

- try to encapsulate the service in question inside the current app

- spike out an internal API just for that service; this API will become the client contract

- wrap an HTTP API around the encapsulation

- make sure I have an ops buddy who can help me at every provisioning and deployment step, especially if this sort of thing is new and a monolith is the status quo

- test the monolith calling itself with the new API

- trial deploy the service and make some cross-cutting changes (client and server) to make sure I know the change process

- start transferring traffic from the monolith to the service

In short, I still don’t think service extraction is as awesome as it sounds on paper. But, if you can get to the point of making a Modular Monolith, and if you can level up your operations to deal with the demands of multiple services, you might successfully pull off (micro)services.

How methodical and quality might keep up with fast and loose

I’ve previously thought that a developer moving fast and coding loose will always outpace a developer moving methodically and intentionally. Cynically stated, someone making a mess will always make more mess than someone else can clean up or produce offsetting code of The Quality.

I’ve recently had luck changing my mindset to “make The Quality by making the quantity”. That is, I’m trying to make more stuff that express some aspect of The Quality I’m going for. Notably, I’m not worrying too much if I have An Eternal Quality or A Complete Expression of the Quality. I’m a lot less perfectionist and doing more experiments with my own style to match the code around me.

I now suspect that given the first two developers, its possible to make noticeably more Quality by putting little bits of thoughtfulness throughout the code. Unless the person moving fast and loose is actively undermining the quality of the system, they will notice the Quality practices or idioms and adopt them. Code review is the first line of defense to pump the brakes and inform someone moving a little too fast/loose that there’s a Quality way to do what they’re after without slowing down too much.

Sometimes, I’m an optimist.