Great albums: Endtroducing

Endtroducing is my canonical example of a revealing album. I heard “Building Steam With a Grain of Sand” completely accidentally in a college business writing class, of all places. A fellow student used it in their presentation, ironically. Afterwards, I asked “what was that?!”, my mind still blown.

I downloaded it and was immediately like “wow”. A whole new angle on music became apparent. I was vaguely aware that hip-hop quotes other music, but didn’t really understand sampling. I’m just old enough that hip-hop has always been a thing. But this was so different, like an other-worldly quote-fest. But, in a good way. A great way, even.

I later learned Endtroducing is notable in that it was made manually. Ableton didn’t exist, so if you wanted to change tempos on samples, you had to pitch correct them yourself. You didn’t have to tape splice anymore, thankfully. But it was still far tricker than making this album would have been today.

This album would spark many musical explorations. Mash-ups like A Night at the Hip-Hopera. The Roots, J Dilla, Soulquarians, and a myriad of other artists. “Building Steam With a Grain of Sand” sparked amazement, curiosity, and appetite for more music I was previously unaware of.

Great albums: Beethoven Symphonies No. 7 & 8

These are my favorite of Beethoven’s “more approachable” symphonies. Symphony No. 9 is my favorite, but it requires a bit more context to take in. Further, it’s a solid seventy minutes of music, ramping up the difficulty of attention span.

Symphony No. 7 (hereafter Seven, etc.) is my favorite outside of Nine, which is sort of its own pivotal thing. It’s a definitive no-skip symphony. Every movement is sublime in its own way. The first movement for its vigor and speed. The second for its solemn opening that builds and builds into a big, emotional moment. The third for its frolic. The final movement for feeling several minutes of emphatic, resolving punctuation and resolution.

Symphony No. 8 has a wonderful opening. The structure and melodic quality is closer to what came before Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1. It sounds like a nod back to Haydn or Mozart, Beethoven’s predecessors. But the harmony and orchestration is distinctly of Beethoven. It’s a great bridge from Beethoven’s Very Good symphonies to his Amazing Symphony Number 9, The One with Ode to Joy (not the official title as recognized by music historians).

These two symphonies fit together really well on CDs. So, you can find basically any conductor/ensemble you prefer performing it. I listened to the Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic version when I was playing music in high school. I’ve found this piece easy to hear little variations between conductors, so if that’s your thing, queue up a few interpretations and go hunting for little distinctions!

What makes a great album

There are four-ish kinds of great albums, in my mind:

- Pivotal albums: the artist or genre was distinctly different before and after the album came out. e.g., classical music was distinctly different after Beethoven, particularly Symphony No. 9

- Revealing albums: pivotal to my perspective or knowledge of music. e.g., my understanding of hip-hop was distinctly different after I heard DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing

- Consistent albums: no track justifies skipping, you can listen to the thing end to end, every time. e.g., Tom Petty’s The Last DJ

- Under-rated albums: albums that are outshined by their extraordinary peers or contemporaries. Most folks know that Born to Run is great, and all other Springsteen albums (generally) rank below it. But that shouldn’t let otherwise excellent and out-of-sequence later albums like The Rising or Human Touch go unnoticed.

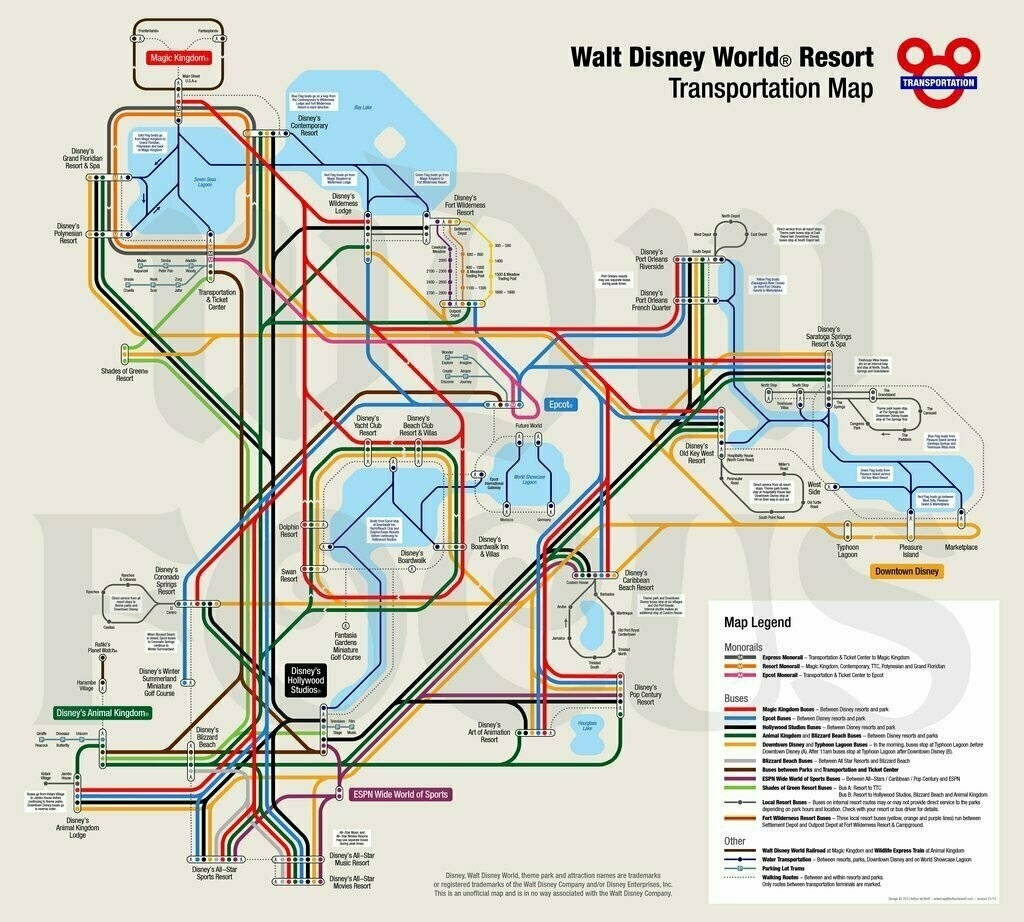

The finest transit system you’ll ever find in a swamp

Imagine all the busses, boats, monorails, trains, and gondolas in Disney World as (quasi-public) transit system. Then make a transit-style map of said system. It’s fun, but a little dismal once I think about it.

Walt Disney World has significantly better transit than most cities in the US.

America’s fantasy world, it turns out, is a place you can get around without getting into a car.

Definitely a top 10 reason (but probably not top 5) I enjoy and find Walt Disney World so intriguing.

Adjacent: if the best transit system many middle/upper-class Americans will experience is a rigorously-top-down, corporate quasi-state, well, that’s a pretty sick burn on capitalism.

“A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It’s where the rich use public transportation” — Gustavo Petro, Mayor of Bogotá

Better know a standard library

Read your current/new language’s standard library. Highly recommended for developers of all experience levels. You’ll pick up the idioms, you’ll discover something useful. You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll wonder if they’re making a sequel!

My favorites are prelude.hs (which, sadly, does not seem to be the file that Haskell bootstraps itself from any more 🤔) and Rubinius’ implementation of Enumerable in Ruby.

(The reference is from The Colbert Report, which is a fun-but-dated thing to know.)

Very famous white guys from history who were not famous for, but known to bite pianos: Thomas Edison and Ludwig van Beethoven.

Offloading fast operations in Ruby by data structure

Noteflakes: A Compositional Approach to Optimizing the Performance of Ruby Apps — the idea is to offload “inner-loop”-type operations from Ruby to C-extensions. The clever twist is this happens via data-structure-as-language. Ruby being Ruby, you can wrap a DSL around the data structure generation to reduce the context switch from Ruby to offloaded operations.

There’s precedent to the approach: if you squint, it’s not unlike offloading the math for computer graphics or machine learning to a GPU. That said, the speed-up is unlikely to be as dramatic.

I hope to hear more of this approach in the future!

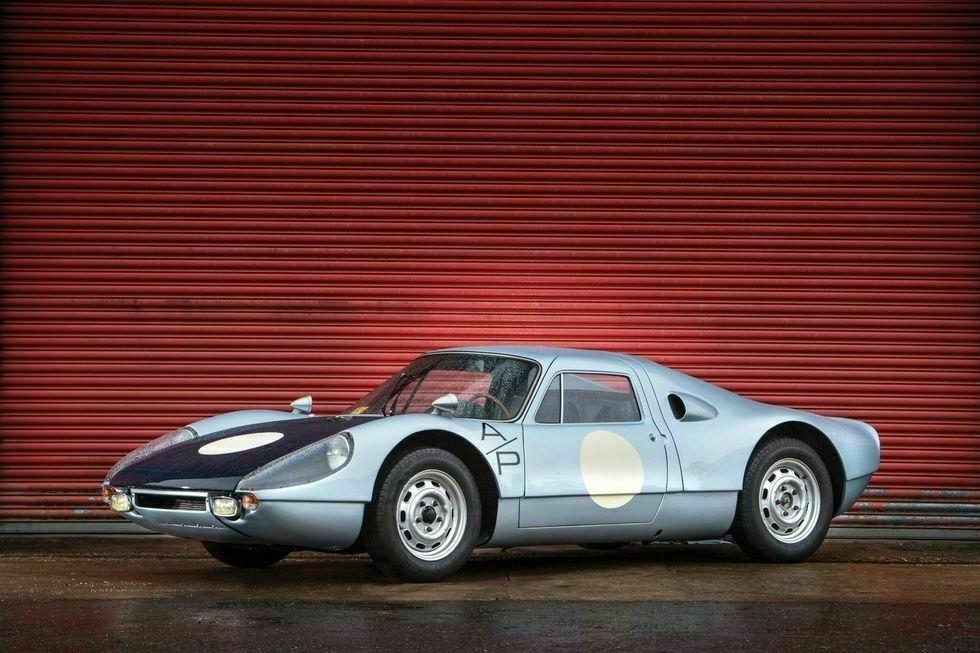

Before the Porsche 911, there was the 356…and the 904. It a looker!

Back in the ’60s, you could buy a street-legal version of Porsche’s top racing car. And just, ya know, drive it on the road! They are pretty pricey today, but at least the auctions have great photos.

Don’t be spooky

It’s possibly the best advice for managers I've given so far. When you’re communicating with your team, lead with context and reassurance. Never message someone on your team, "let's talk when you get a minute". That's void of information and scary as heck!

I have to remind myself of this when I'm rushing. It's faster to ping someone to arrange a synchronous talk than it is to write out what I need to say and cover all the bases. But that doesn’t give me license to skip all the context. Broad strokes are okay. An information vacuum is not okay.

Accidental spookiness invites story-crafting. Minds race. Lacking information or context, we tell stories. They often aren’t happy stories, regardless of how good your relationship with the team. We humans are better at convincing ourselves to fear something (survival instinct) than the other way around.

Avoiding spookiness reduces the chance of people telling themselves negative stories. Context and clarity counteract reading the tea leaves and world building. Even more important, it prevents people from pre-gaming the conversation. That way, they don’t prepare for a conversation that happened in their heads, instead of one that’s about to happen. (Avoiding pre-gaming is important on both sides of the conversation, as it turns out.)

A corollary to “don’t be spooky” — deliver constructive but critical feedback as close to the “original sin” as possible. Receiving feedback that you did poorly weeks after the fact is disconcerting. It can lead the recipient to wondering what other things they’re doing poorly but won’t hear about until later. Which leads to story-crafting, and the whole negative cycle starts a-new.

Give your team enough context to pre-game conversation based on the real context, not conjecture. And don’t hold on to feedback for “that perfect time”.

Would you pay more for a noisy computer?

Computers should expose their internal workings as a 6th sense, Matt Webb:

I kinda miss the days when I could hear the hard drive of my computer. If it was taking a while to response (say, when opening a big file), there was a difference between the standard whirr chugga chugga ch-ch-ch chugga seek pattern, and a broken kik kik kik. And you’d have an idea how long loading a file from disk should take, versus the silent “thinking” time afterwards.

…

The point is not the sound. You barely noticed the sound.

The point is that you felt you like were in psychic communion with the workings of the computer.

1.

Watch and car enthusiast/collectors go wild for these qualities. They go on and on about the shape of the Jaguar E-Type, the roar of an American V-8 engine, the howl of a Formula 1 V-10 engine, the smell of new watch strap leather, the classic looks of an Omega Speedmaster or Rolex Daytona.

And then there’s the “save the manuals” crowd! Despite knowing that modern transmissions are more effective than any human, they desire the involvement of controlling a major interaction between the car’s engine and the rubber meeting the road.

Another crowd revels in and/or yearns to own one of the “last analog” of some sort. The Last Analog Ferrari/Porsche/BMW/etc. It’s a desire for a sensory experience at the expense of outright speed/efficiency, a True Scotsman argument, and a lot of nostalgia. It’s also nice that “analog” cars can’t become haunted my misbehaving computers or software.

2.

Computers (and their distant cousins, the electric car and smartwatch) are left only to simulate these qualities. A smartwatch could display the same information as an Omega Speedmaster and replicate its design down to pixel perfection. It will never catch the light like a physical watch will. Porsche’s Taycan electric car makes its own kind of howl (if you pay slightly more for the option), but it pales to any era of their gasoline engines.

A lot of these watch and car qualities come down to nostalgia. On paper, a CO2 producing, endlessly vibrating machine full of moving parts that are going to break is inferior to the electric car designs of 2021. What we need is a new sort of romance as we transition from moving parts to entirely solid state machines.

Computers could make us feel something. They should tap us once if something works, or tap us a few times when something needs our attention. We should be able to tell they’re working hard, or hardly working, by the sounds of their insides clicking, whirring, or churning. Data and files that have gone untouched for a while should have a faded patina.

In particular, there’s room for moving from Apple Store austerity/minimalism to color and form-follows-function ornamentation.

3.

Cultured Code’s Things is my go-to example. They’ve gone to the trouble of re-implementing large swaths of the UI toolkit Apple provides on their platforms. The attention to detail shines through. Every action has the slightest haptic feedback. Swiping and tapping through the UI has a hint of physical heft, as though there’s a bit of momentum to scrolling around, opening up a task, or flipping over to the navigation “sidebar”. It’s the best use of animation I’ve seen on the platform. It’s still quite austere, but at least there’s a feeling that it’s not a UI floating in Jony Ive’s featureless, zero-gravity void!

I suppose the jury’s out whether patina, “this is my computer, none are like it”, and collectability are out the window too. Maybe this whole crypto-token thing will bear fruit without extending humanity’s use of coal power far beyond its past-due date.

4.

There’s another angle here. To continue the car metaphor, most people don’t want a sports car or muscle car. They don’t even want an SUV with a muscle-car engine. They want something reliable, convenient, and affordable.

Folks mostly want appliances. Solve this problem for me with a minimum of showmanship or drama. That is, they want a quiet and unassuming car or computer. Normal operation should make no sound at all. Worrisome noises should only happen if things worsened after warning the owner and the machine remained quiet.

Solid state computers and cars are unavoidable, as futures go. There’s no reason to go back to combustion, cooling fans, and extensively spinning disks. Computers as appliance are largely here and largely preferred. Watches are in the midst of that transition. Cars are next on the wave of change.

5.

Maybe this all comes down to computers-as-invisible-fabric-of-life vs. computers-as-central-tool. Glass walls that show off the mainframe/server/datacenter room (not unlike glass engine covers on McLaren/Ferrari/Lamborghini supercars!) vs. servers sequestered behind anonymous drywall or offsite completely “in the cloud”.

Someday, we’ll get past computers as we know them now. Then we’ll have “computer-punk”. Like steampunk before it, we’ll imagine life if we’d advanced in knowledge and ethics but not technology.

Probably, if I see that future, I’ll have some fleet of computers, mostly invisible, which I use as my “daily driver” for getting stuff done. But if current trends continue, I’ll spend a few hours a week enjoying a “weekend computer” that is clack-y, slightly anachronistic or nostalgic, and gets noticeably huffy when I ask too much of it.

Into the Miles-verse

I’m kicking off a new “listening project” - Miles Davis. Inspired by A Beginner’s Guide to Miles Davis, I’m going to grind my way through the Miles-verse in chronological order. For posterity, my favorites from before this journey are Sketches of Spain and Bitches Brew.

(I think Kind of Blue is properly rated but not noteworthy because it’s the jazz album that everyone knows and reveres, whether they like jazz or not. And, rightly so.)

Previously in listening projects:

Circa 2008, I got a little bored/annoyed with what I was listening to and decided to play through all the songs in my iTunes library, in order by artist. Discoveries (to me) lurking therein: Bruce Springsteen Born to Run, Talking Heads, Stop Making Sense. Getting through the B-artists was a real endeavor. I have a lot of Ben Folds, Beethoven, Billy Joel, and Brahms albums.

Circa 2016, I listened to all of the Radiohead albums in chronological order. I’d previously really only known them as “the Creep guys” and “the dudes who released an album of MP3s way before everyone else”. (But probably not before Prince, who also performed “Creep”, eventually.)

An exercise in CPU design, in the small

Welcome to the OPC series of CPUs, where everything fits on one page - one page each for specification, emulation, HDL. For details see the OPC Project web pages.

Computer architecture, Verilog code to implement the design, simulation and testing of the design, writing an assembler and assembly to test the system. All within my favorite kind of constraint - fitting each component on one page.

They’re not particularly useful machines, but they do de-mystify the bridge from electrical engineering to software engineering.

When I was an intern at Texas Instruments, the tools for this were enormously complex, slow, and expensive. Whole clusters of Sun machines set aside for simulating the upcoming designs and verifying they did the right thing in software. Not to mention the tremendous effort of verifying the design that was coded was possible to build in the company’s chip fabrication plants and processes.

That this depth of tooling is now available to hobbyists would have blown me away in 2002.

Math-y and/or word-y

I'm a developer who (formerly) recoiled at math, especially calculus and matrices.

Instead, I thought, I loved the language-y parts of software development. Programming languages, little languages, domain-specific languages. Designing the names, concepts, and relationships in APIs. Domain-driven design, jargon, modeling. I thought of myself as more of a writer-y developer than a math-y developer.

I suspect that I’m not alone amongst programmers in favoring liberal arts over sciences. Further, I suspect that over the past two decades the number of programmers with science-y backgrounds has steadily declined.

But, it turns out I do a lot more math than I thought! SQL is set theory. Layout is math (mostly about centering things 🤷). State machines reduce many kinds of logic problems to simple, but math-y, flowcharts. Almost every bit of programming one does is logic, which is, you guessed it, math.

And that only covers web apps! Computer graphics is a heck of a lot of trigonometry (and whatever is involved in calculating diffusion of light). Machine learning is lots of statistics plus a little calculus. Type checking in compilers is category and/or set theory.

The flip side is also true: developers who think they only enjoy the math-y parts do a lot more language/liberal artsy stuff than they think. They've got opinions about language constructs, whether a method name is good or not, if an API is easy to use correctly or not. All "soft" non-math-y constructs!

When it comes down to it, it's more likely that poor math education let me down than I am fundamentally not a math person. Related: Why Math Class Is Boring—and What to Do About It:

There are two types of people in the world: those who enjoyed mathematics class in school, and the other 98% of the population.

Following up on recommendations, for the forgetful

It’s hard to land music, books, etc. recommendations from friends because timing is everything. The best case is a recommendation for a thing I didn’t know of and it’s precisely what I need to read or watch at the exact moment. Beyond that, it’s likely I’m reading some 900-page book (humble-brag) or deep into a peak television series (humble-brag) that I’m trying to finish before my attention wanders.

I’ve come up with a couple of ways to more immediately act on recommendations, so they aren’t for naught:

- Download a Kindle/iBooks sample right away and read the first several pages of whatever they recommended. If I’m into it maybe I’ll stick with it. At least, it’s on my backlog of books until I forgot why it’s there and delete it (i.e., 2-3 times a decade).

- Watch the first several minutes of the thing on Netflix or whatever. See if it’s any good instead of watching random YouTube videos recommended by the algorithm.

For everything else, there’s always the long, scary list of things I’d read/watch/play/listen to if we stopped doing billionaires and gave everyone a living wage. 🤷♂️

Craig Mod’s simple search

Craig Mod, Fast, instant client side search for Hugo static site generator:

I believe Fast Software is the Best Software and wanted keyboard-based, super fast search for my homepage / online collection of essays. This method was highly inspired by Sublime Text’s CMD-P/CMD-shift-P method of opening files / using functions.

I love that this is a Gist, an idea floating around. Not to reuse wholesale but to adapt and make your own. More like a recipe, less Professional Software Development 🤵♂️. Not packaged software, almost a thought-experiment wrought of relatively-accessible code incantations.

What makes an excellent design doc

Replicache Detailed Design(https://doc.replicache.dev/design):

Replicache runs alongside your existing application infrastructure. You keep your existing server-side stack and client-side frameworks. Replicache doesn’t take ownership of data, and is not the source of truth. Its job is to provide bidirectional sync between your clients and your servers. This makes it easy to adopt: you can try it for just a small piece of functionality, or a small slice of users, while leaving the rest of your application the same.

Conflicts are a fact of life when syncing, but they don’t have to be painful. Replicache rewinds and replays your transactions during sync, sort of like git rebase.

I haven’t used Replicache, but this design document makes me think it has the qualities that excite me when I discover infrastructural software:

- it solves a tricky problem (distributed application state)

- by compressing the problem down to essential concepts

- those concepts are solved in a way that I can imagine “how would I use this?”

- and writing clearly about that solution

“Rationalize and solve” doesn’t help someone who is venting

If you’re doing the whole servant leadership thing, you’re gonna hear some people venting frustrations. Yihwan Kim, When a 1:1 turns into a vent session:

As an engineering manager, I’m learning that a big part of my job (perhaps my only job) is to help people solve problems. I happen to enjoy solving problems myself. So it’s only natural that when someone starts venting, I want to rationalize the conversation, correct inaccuracies, and discuss actionable next steps.

I always have to remind myself: don’t.

Relatable. It’s easy to react to someone venting by rationalizing and solving. As Yihwan points out, that’s not the card to play here. The win condition for these is to 1) hear your colleague out and 2) help improve the cause of the vent if your teammate wants you to.

4 perspectives on writing

Spoiler alert: it’s all about organizing what they wrote in the past, finding it later, and remixing it into something they need in the moment. 🧠

Austin Kleon, Indexing, filing systems, and the art of finding what you have: writing is meticulously indexing what you may have jotted down in the past. Come for the bit on classic American authors, stay for Phyllis Diller and Joan River’s massive card catalogs of jokes! 🤯

Cory Doctorow, Writing is accumulation: it’s easy when you accumulate a pile of text files from blogging over twenty years. He searches and surfs tags to find material for whatever he wants to write about today. An external brain.

That’s how blogging is complimentary to other forms of more serious work: when you’ve done enough of it, you can get entire essays, speeches, stories, novels, spontaneously appearing in a state of near-completeness, ready to be written.

Shawn Wang, Mise en Place Writing: writing is like cooking. Separate the preparation/creation and the cooking/editing.

By decoupling writing from pre-writing, I can write more, faster, and better.

Nat Eliason, Tactics to Help You Become a Better Writer: writing is rules. The better your rules, the better (and more) your output.

One priority is like wind in the sails

It’s true that I can scale myself, teams, and organizations to walk and chew gum at the same time, but it is surprisingly effective to focus on one thing at a time. This is the essence of “priority” — put all my energy into one outcome until it’s done. Then the next one, the next one, etc. as my efforts start to compound.

I, like many folk, do much of my best work in coffee mode. When that deep, coffee mode work aligns with my priority, everything is operating smoothly and life is good. If my priority (singular) changes and I need to go deep on something else, that’s not ideal but not so bad either. As long as I can still focus, things are good. When I’m asked to go deep on two things or pulled to work on deep but unaligned tasks, that’s when things get gnarly.

A useful activity that looks like (and is often called) prioritizing is sorting (“triaging”) a list of potential work by what’s most impactful or important. This is more of a planning activity than a priority exercise. It acknowledges there’s a lot to do and time is finite. The result sends a clear signal: this thing at the top of the list is more important than all the things below it. In particular, any of the top items are more useful to work on than all the things further down the list.

Get better at finishing projects. That’s working smarter, not harder. Finished projects, axiomatically, don’t need prioritizing against other work. Limiting work in progress is difficult to pull off in the moment but a crucial tactic to apply when things get intense.

Possibly controversial: multiple priorities is about the same as having no priorities. The trick that priorities pull is freeing us of the energy-sapping process of deciding what’s most important and what trade-offs to make. A single priority is a note from your past, well-considered self saying “this is more important than all the other things; work on it before anything else”.

Systems of “one priority”:

Multiple priorities make it unclear what expectations are for individuals. Choosing what to work on becomes difficult and a burden. A single priority is a mission, a clarity of work. Get this thing done, declare victory, move on.

Desktop vibes

I’ve got three “virtual” desktops going on my Mac right now. The idea each is its own functional workspace. I don’t have three separate physical workspaces to do my writing/thinking, coding/building, or communicating/collaborating. So a digital approximation is the second closest thing. 🤷♂️

Leftmost is where I do the thinking. The background is one of the “scenic” images included in macOS. The idea is, if I had a little writing hut, ala Thoreau in Dickinson for looking off into the distance and plying some kind of writing craft, this is the kind of thing I would see when I look up.

Rightmost is where I communicate with the world and my colleagues. The background is also a built-in macOS dynamic desktop of swoopy, abstract colors. Like John Oliver comes to our living room from a featureless void, so I think of this desktop. Ideas, questions, and data points come to me from the void of the internet, end up in this imagined space, and I respond to them in turn through this medium and back to the void. Heavy, eh?

In the middle is where I do the building and coding. The background here is a flat color. I got it by color picking a photo of the 12-Gauge Garage. I noticed later that it’s close to “go away green” as used in Disney’s theme parks to draw the eye away from backstage areas where the magic may be in-progress or under-repair. The idea is I shouldn’t really see this background. I should focus on whatever I’m coding/testing/making/etc.